Author’s Note, 26 April 2021: This essay of 20 pages was originally written three years after the open invasion of Iraq in March of 2003. Various privatizations of warfare and security-services were already showing themselves, under new conditions of technology and finance. This essay is a sequel to an earlier essay by the author, entitled: “Setting Just Limits to New Forms of Warfare.”

Dr. Robert Hickson

29 October 2006

Festum Christi Regis

The Crescent Phenomenon of the Privatization of Warfare and Security-Services:

New Oligarchic Feudalities, Special-Operations Networks, and Ambiguous Mercenaries in a Time of Borderless Economies and Finance

This essay on the arguably grand-strategic – but unmistakably permeating – privatization of “military and security services” constitutes a short sequel to an earlier strategic essay, entitled “Setting Just Limits to New Methods of Warfare.”1 This aggressive sequel might also be entitled “Setting Just Limits to Old Methods of Warfare under New Conditions of Technology and Mammon.”

It proposes to be especially attentive to the Corporate Governing Class and their “Managerial Elites” (in the discerning wise words of the late James Burnham). Indeed, these new luring conditions of technology and wealth are to be found, as it is herein tenaciously affirmed, conducing especially to the monetary advantage and added perquisites of the Corporate, often Trans-National, Nomenklatura and their mobile, often unaccountable, Managerial Elites. This lure of new advantages and influence (with little accountability) will also likely attract the closer inextricable involvement of the tax-exempt, strategic-cultural Foundations and their own Governing Elites, not only in the United States, but also in other areas of “Mandarin” or “Democratic Centralism.” To what extent, we may well ask, are we witnessing the formation of New Feudalities with their own special Patronage System – and with new possibilities of collaboration between the “Overworld” (or the “Overlords”) and the “Underworld”?

Surprisingly, even a cautious professor from Duke University, Peter Feaver, who now serves on the staff of the National Security Council in Washington D.C., candidly admitted at an October 2004 Conference on “The Privatization of American National Security”:

In fact what we’re seing is a return to neo-feudalism. If you think about how the [British] East India Company played a role in the rise of the British Empire, there are similar parallels to the rise of the American Quasi-Empire.2

This grand-strategic (not just “military-strategic”) matter of the “military-merchant banker” apparatus of the East India Company was not only important historically. It will also likely be very important strategically in the near future, especially in its new embodiments under the current conditions of finance and technology. Scientific and technological elites – also the Managerial and Higher Elites in the financial world – are prepared to help “the Military-Industrial Complex” in new ways, and maybe also for the sake of our seemingly advancing American-Anglo-Israeli Empire, proposing, as well, the advance of a “New Mercantile Order” (in the approving words of Jacques Attali, the French Socialist, in his admiring biography of the “super-capitalist,” Sigmund G. Warburg).

In President Eisenhower’s once-famous Farewell Address (January 1961), he warned his audience of two special and growing dangers: not only what he called “the Military-Industrial Complex,” but also what he designated as “the Scientific and Technological Elite.” Although the former formulation, known also as “the M.I.C.,” became more widely used and better understood in later years (and not just in Left-Wing Circles), President Eisenhower himself never elaborated upon what he really had in mind concerning this more specific danger of the Scientific and Technological Elite. Given the modern propensity for “social (and psychological) engineering,” it certainly included the then-growing fields of Mass-Media Studies, Cybernetics and the Information Sciences; and their applications in human psychology, commercial-political advertisements, semiotics, and finance, to include the growth of encryption systems and the consequent scope they gave for secrecy, deceptive manipulation, and “money-laundering.”

The phenomenon of Mercenaries or Soldiers of Fortune is an immemorial practice to be seen in various cultures down the course of history, whether as individual soldiers “for hire” or as larger “free companies” and even as “secret armies.” Carthaginian mercenaries from Spain and Sardinia, or Greek mercenaries in Persia, for example – and as they were also later used by the conquering Philip of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great – are well known to students of Greco-Roman history.

Mindful of the recent book, America’s Inadvertent Empire (2004),3 we may comparably recall the Carthaginians and their inattentive (and inordinately complacent) resort to mercenary forces:

Meanwhile Carthage grew pre-eminent, and as she grew, manifested to the full the spirit which had made her …. And everywhere they [i.e., these questing Carthaginians under sail] sought eagerly and obtained the two objects of their desire: metals and negotiation. In this quest, in spite of themselves, these merchants, who could see nothing glorious in either the plough or the sword, stumbled upon an empire. Their constitution and their religion are enough to explain the fate which befell it. They were governed, as all such states have been, by the wealthiest of their citizens. It was an oligarchy which its enemies might have thought a mere plutocracy …. To such a people the furious valour of the Roman and Greek disturbance must have seemed a vulgar anarchy …. It was characteristic of the Carthaginians that they depended upon a profound sense of security and that they based it upon a complete command of the sea …. The whole Maghreb, and, later, Spain as well; the islands, notably the Balearics and Sardinia, were for them mere sources of wealth and of those mercenary troops which, in the moment of her fall, betrayed the town …. The army which Hannibal [i.e., “Baal’s Grace”] led recognised the voice of a Carthaginian genius, but it was not Carthaginian …. The policy which directed the whole from the centre in Africa [i.e., from Carthage] was a trading policy. Rome “interfered with business” …. The very Gauls in Hannibal’s army, for all their barbaric anger against Rome, were [justly] suspected by their Carthaginian employers.4

This Mammonite Maritime-Merchant Empire truly paid for its mercenaries – who were contumaciously troublous and finally perfidious, multicultural mercenaries, indeed.

But, we may also recall the famous Swiss mercenaries, at least until the 1513 Battle of Marignano; the Irish “Wild Geese” in seventeenth-century Spain and elsewhere; the English and American “privateers” and Italian “maritime mercenaries” (or “mercenaries of the sea”); the “condottieri” of Italy; the Hessians; the French Foreign Legion; the British use of the Gurkhas from Nepal; various military secret societies of China and Japan (to include the Chinese “Triads” – or “Tongs,” like the 1900-era “Boxers” – and the current Japanese and Korean “Yakusa”); all the way up to Private Military Companies of more recent times, like Executive Outcomes, Sandline International, Blackwater, Triple Canopy, Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI), and Kellogg, Brown, and Root (KBR), a subsidiary of Halliburton.5

To quote the summary, introductory words of Michael Lee Lanning’s recent book on the concept and reality of “mercenaries”:

They go by many names – mercenaries, soldiers of fortune, wild geese, hired guns, legionnaires, contract killers, hirelings, condottieri, contractors, and corporate warriors – these men who have fought for money and plunder [or other perquisites] rather than for cause or patriotism. Soldiers of fortune have always played significant roles in warfare, they are present on the battlefields of today, and they certainly will be a part of whatever combat occurs in the future.6

The sophisticated incorporation of mercenaries into what has been called “the Military-Industrial Complex” is – and morally should be for us – a troubling development, especially with their new access to and elusive application of “Special Technical Operations” (“STO”), which often involve the unique and sometimes unrepeatable use of a particular nation’s “Technological Crown Jewels”. However, in the rather cynical, but thoroughly “progressivist,” view of Michael Lee Lanning:

From huge, publicly owned firms to small independent companies [i.e., “military companies”], the corporate world has learned that war is indeed good business, and business is good and getting better.7

Nonetheless, this is a phenomenon which often must be strongly, but yet discerningly, resisted – and not fatalistically or lethargically accepted as irresistible and as already overwhelming and “beyond control.” Moreover, it is often the case that “organized crime is protected crime,” that is, protected by certain political and financial elites.

Furthermore, to what extent does a well-paid “all-voluntary force” itself represent and promote (or at least conduce to) the broader “mercenary phenomenon” of which we speak?

For, the concept of the “all-volunteer” military – which was first re-established in the U.S. during the final years of the Vietnam War, in 1973, and just after the United States had itself ended the military draft – inherently promotes, it would seem, a structure of incentives which often enough suggests an elite “mercenary force” to be used “on call,” in readiness for many rapid “expeditionary missions” or other worldwide “special operations.” Such a volunteer force easily becomes more separated from the common citizenry and their own proper sense of duties and those selflessly sacrificial commitments which are so necessary for the true common defense of the nation: i.e., an integrated strategic “defense-in-depth” of the Homeland – i.e., of the home “base” and of its manifold essential “communications,” to include our “sea lines of communication” and important “undersea cables and nodes.”

Moreover, it is all too easy to employ an all-volunteer force without the deeper moral engagement of the whole nation. Thus, the citizens – given the propensities of our human selfishness – may all to easily say: “Well, they volunteered for these hazardous duties; it’s not really our special concern.” Such an insouciant attitude certainly does not appear to be an adequate, or even a responsibly attentive, orientation to meet the Constitution’s specific requirement: “to provide for the common defense,” and unto the greater common good. Such an indifferent orientation tends towards a fragmentation or segmentation of the larger society, and even into the tripartite “Neo-Gnostic” division (in the “Information Age” words of Michael Vlahos), a division between “the Brain Lords,” “the Upper Servers” (or the new Praetorians), and “the Lost” (or “the Masses”). What, for example, is the concept of citizenship in such an “over-specialized” and “compartmented” society? What is the likely sacrifice for and common participation in the common good, and not just in defense of the Elites or of the elusive “public interest,” which is already vague enough?

Lanning himself makes a pertinent observation in this context of an all-voluntary military, and considers further its long-range implications, especially in the matter of the financial bonuses currently given to both citizens and non-citizens, both men and women, who are now active members of the U.S. Armed Forces and serve “in units rotating in and out of Afghanistan and Iraq”:

It would be unfair to the many brave men and women [who were, already in early 2002, 15% of the overall Army!], both citizen and noncitizen, who accept the [larger military] bonuses [for “volunteering to extend their tours” overseas] to question their patriotism or their commitment to their country. However, it would not be unfair to note that increased pay, citizenship [granted to non-citizens in the military, after a certain period of “service”], and other benefits in exchange for enlistment [or voluntary extensions of duty] are not all that different from the reasons [the motives, the incentives for which] soldiers of fortune have fought since the beginnings of time.”8

The all-volunteer military was itself, it would seem, also an effective psychological and cultural preparation – “a psychological preparation of the battlefield” – for the further strategic and tactical recourse to military privatization and to those commercial and financial incentives which this now more organized, new, corporate phenomenon has so generously and profitably provided! And which seems especially remunerative and risk-free for the corporate elites themselves, and not so much for the short-term, high-paid “young adventurers abroad.”

When most people recall the discussion over the last ten or fifteen years about “privatization” in the military, they probably think of the phenomenon of “outsourcing,” sometimes called “farming out.” This proposed and soon expanding “outsourcing” first meant the “contracting out” to civilian contractors of certain traditional military functions such as “recruiting,” “food preparation,” “clean up,” “personnel services,” and certain kinds of logistical functions of “supply, maintenance, and transport.” It was thought (or euphemistically “propagandized”) to be an enhancement of “cost effectiveness” and “efficiency,” so that the military could purportedly concentrate on its more essential missions of “training, readiness, operations, and combat.”

Initially these new “managerial” proposals seemed plausible and even attractive, though some people, more historically informed and far-sighted, wisely saw that the long-standing and much-tested tradition of a “self-policing military” capable of operating as an independent and self-reliant and coherent entity abroad, especially in “denied areas,” was being subtly undermined. And, from the outset, certain perspicacious questions were raised.

For example, would such civilian contractors, after “releasing a soldier for combat,” also still deploy with the military into combat zones? Would they also easily and willingly go to various remote and dangerous areas overseas, and then persevere, even after combat and in the graver times of instability and uncertainty and insufficiency? And then, what would be their status, according to the laws and conventions of land warfare, especially if they were to be captured? Would the U.S. Military also, for reasons of purported “expedience,” come to hire “foreign nationals” to help their military operations and support missions overseas? Moreover, would our covert (“black” or “gray”) Special Operations Forces, for example, have foreign “food providers” even in their Forward Operating Bases – such as (hypothetically) cooks at a covert base in Qatar? And what about the consequent security problems, to include the matters of both Operational Security and Communications Security? Or would we preferably ship American civilian-contractors to these overseas locations – such as “vehicle mechanics,” “construction engineers,” “mess hall” cooks and stewards, and even female barbers and nurses, especially from our domestic U.S. military bases, who were, as is commonly known, already being sent overseas in 2002 to Uzbekistan and other nearby areas?

However, these discerning questions constitute only a beginning to a fittingly deeper examination; for, these initial concerns were even still somewhat “on the surface,” especially when we consider, in the longer light of history, the special dangers and “lessons that are to be learned” from those earlier “strategic, para-military, merchant-banker joint stock companies,” such as the British East India Company, as well as their Dutch and French counterparts.

For, when we even briefly examine how some earlier Empires all too promiscuously (but quite seductively) resorted to such military-commercial-naval instrumentalities to enhance their wealth and power – namely, their overseas colonization, their access to raw materials (including gold), and their prosperous trade in special commodities, and even their inherently corrupt and nation-destroying criminal involvement in the “drug trade” (as in the corrupting British Opium shipments from India into China, which caused the protracted “Opium Wars,” which the Chinese have never forgotten, nor seemingly forgiven) – we should have great pause, indeed, at our own incipiently analogous developments.

By such an historical-strategic inquiry we may thereby come to understand how and why these earlier and also current “Arcana Imperii” worked (i.e., their more secret doctrines and methods of imperium or exploitative hegemonic rule), so that we may then intelligently and persistently resist them today and all of their metastasizing corruptions and treacheries. The military has always been an instrumental subsidiary of these larger schemes of dominance, and they are still so utilized today, though now under newer forms of “privatization” and aided by some new kinds of special weapons that are rooted in very advanced, new technologies, thereby enabling them to conduct “special technical operations” with great subtlety and secrecy and “plausible deniability” – and even with long-range environmental and genetic effects.

The newer forms of military “privatization” imply much more than just the traditional phenomenon of “soldiers of fortune,” “mercenaries,” or “privateers” with “letters of marque” – something also more pejoratively and bluntly known as “pirates” or “buccaneers”! The scientific and technological elite may now more easily make and sustain “strategic combinations” with the sophisticated corporations of “the Military-Industrial Complex,” in order more deftly to employ “private military companies” over a wide spectrum of overt – and also covert – operations.

By way of further preparation for our deeper grasp of these new “combinations,” some considerations of that earlier military history will first help us better to understand – especially in order to differentiate and then to resist – these troubling developments: not only what is still continuous from these well-established historical origins, but also what is new in the current analogous privatization of warfare and its related “security services.” For, police and military realms are now increasingly intermingled, and there is also a growing “seam” between war and criminality – part of the growth of unlimited irregular warfare, or what the Chinese have called “unrestricted warfare.” It is also part of the competition and strategic initiative “to set the rules” – to set and control the new and operative “conceptual terms and legal rules of engagement” in the wider spectrum of “future forms of warfare.”

The “Emerging American Imperium” seems more and more prone, it would appear, under current conditions of technology and encrypted information, to resort to methods and organizations which were once analogously used by the Emerging British Imperium, such as the British East India Company, especially under the eighteenth-century colonial military leadership of Robert Clive, and as aided by its long-standing, resourceful association with the Bank of England itself (which was founded only in 1694).

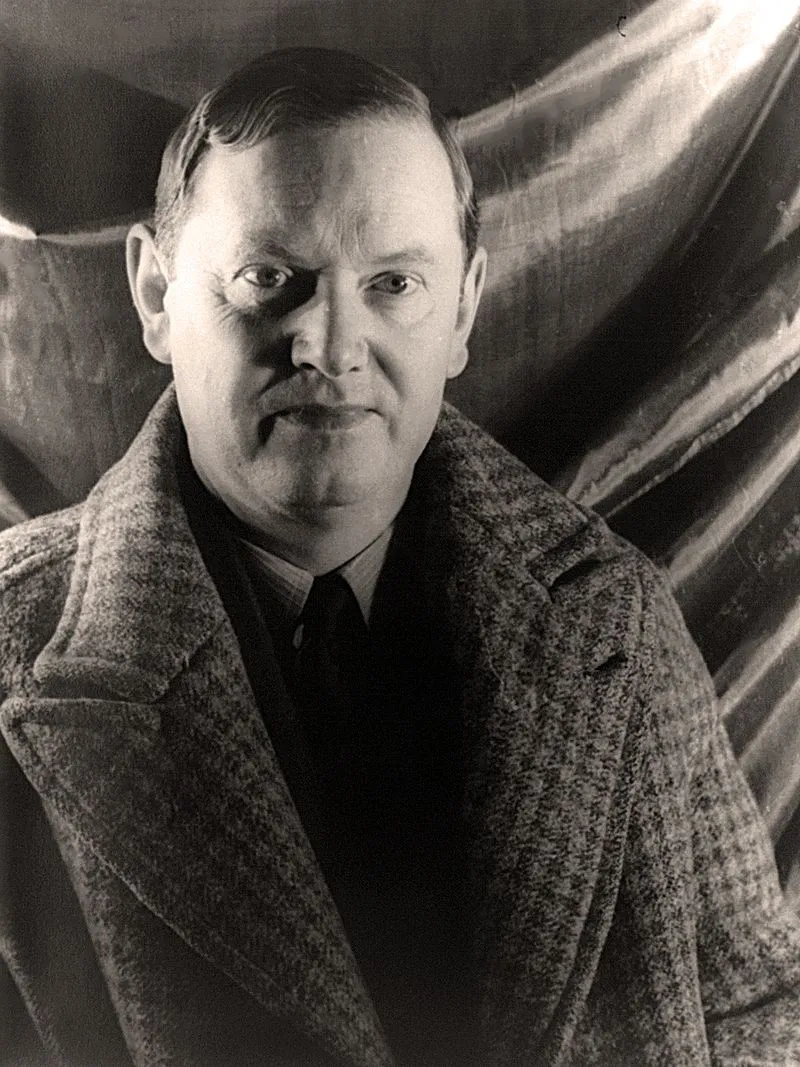

Two finely connected sets of insights from General J.F.C. Fuller will, in this important context, help illuminate the current developments in military privatization and its likely formation of new loyalties, new feudalities, and a new ethos and culture: namely a “monetary” and “mercantile ethos” of “the cash connection,” in increasing subordination to the new Lords of Mammon, the New Grand-Strategic Overlords. The public good of a particular historical nation, for example, may come thereby to be subordinated more and more to the service of new Masters of Trade, or to the Global and Quasi-Feudal Lords of High Finance. This new Mercantile Order, which includes the influential continuity of certain well-connected families and financial Dynasties, will themselves likely require more and more military protection, both in defense and for the offense; as well as variously versatile, investigative and secret “security services.”

In the strategic conclusion of his chapter on the Battle of Blenheim (1704) and its momentous consequences, General Fuller says the following, concerning the War of the Spanish Succession, and from his own Military History of the Western World:

It decided the fate of Europe, and as Mr. Churchill writes, “it changed the political axis of the world….” For England, Blenheim was the greatest battle won on foreign soil since Agincourt [1415]. It broke the prestige of the French armies and plunged them into disgrace and ridicule …. and at Utrecht a series of peace treaties was signed on April 11, 1713…. Further, he [Louis XIV] recognized the Protestant succession in England [against the political legitimacy of the Catholic Stuart kings] …. Of all the booty hunters, England obtained what was the lion’s share: … and [hence] from Spain, Gibraltar and Minorca, which guaranteed her naval power in the Western Mediterranean. Further, an advantageous commercial treaty was signed between England and Spain, in which the most profitable clause was the grant to the former [i.e., England] of the sole right to import negro-slaves into Spanish America for 30 years.9

General Fuller, before moving on to even more consequential matters, adds an important footnote about this corrupt network of manifold smuggling, which included the inhuman slave trade:

The Asiento or “Contract” for supplying Spanish America with African slaves, … permitted the slave traders to carry on the smuggling of other goods. “This Asiento contract was one of the most coveted things that England won for herself and pocketed at the Peace of Utrecht.” (Blenheim, G.M. Trevelyan, p. 139)10

Moreover, says General Fuller:

With the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht, England was left supreme at sea and in the markets of the world, and as Admiral Mahan says, “not only in fact, but also in her own consciousness [an unmistakably prideful imperial consciousness!].” “This great but noiseless revolution in sea-power,” writes Professor Trevelyan, “was accomplished by the victories of Marlborough’s arms and diplomacy on land [i.e., by John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough (1650-1722), victor at Blenheim] … it was because Marlborough regarded the naval war as an integral part of the whole allied effort against Louis [King Louis XIV of France], that English sea power was fixed between 1702 and 1712 on a basis whence [as of 1955] no enemy has since been able to dislodge it.”11

Later, he adds: “Sea power was, therefore, the key to the colonial problem.”12 For example, “in the struggle for trade supremacy in India,” the “command of the sea” was decisive, for, under the geographical and technological conditions of that age, “whoever commanded the sea could in time control the land.”13

Concluding his important strategic analysis, not only of British sea-power’s “noiseless revolution,” but of something of even greater moment, Fuller says:

But the revolution went deeper still; for it was the machinery of the Bank of England [founded on 27 July 1694] and the National Debt [which significantly began only in January 1693] which enabled England to fight wars with gold as well as iron. William’s war [King William of Orange’s War] had lasted for nine years and had cost over £ 30,000,000, and the War of the Spanish Succession [concluded by the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht] dragged on for 12 years and cost about £ 50,000,000. Only half this vast sum of £ 80,000,000 was met out of taxation, the remainder was borrowed [from the High Financiers who had leverage over the Bank of England and thus held the Sovereign at risk] and added to the National Debt. Thus a system was devised [sometimes called “Sovereign Risk” and its accompanying “Fractional-Reserve Banking”] whereby the prosperity of the future was underwritten [or mortgaged!] in order to ease the poverty of the present, and war was henceforth founded on unrepayable debt. The banker merchants of London steadily gained in political power [“le pouvoir sur le pouvoir” – Jacques Attali] over the landed interests, and, therefore, increasingly [as is still the case today] into their hands went the destinies of the nation and the Empire, whose frontiers had become the oceans of the seas.14

Naval power and the power of High Finance and the Manipulation of National and Foreign Debt was a very powerful combination indeed! Military and naval leaders allied themselves with “the Banker Merchants” – perhaps also as it is the case today, more and more.

After 1713 – and especially after Clive’s decisive Battle of Plassey in 1757 – Britain expanded the use of its other strategic instrumentalities, such as the earler-founded “private” military-merchant joint-stock company in India, which was also known as the British East India Company.

General Fuller will again help us consider the long-range implications of the East India Company’s quite momentously decisive battle in 1757, the Battle of Plassey, conducted in northeast India on the “shifting banks” of the Bhagirathi River – only some forty-four years after the Treaty of Utrecht:

What did this small battle, little more than a skirmish accomplish [a battle which was led by Robert Clive (1725-1774)]? A world change in a way unparalleled since on October 31, 331 B.C., Alexander the Great overthrew Darius [the Persian] on the field of Arbela. Colonel Malleson, a sober writer, says: “There never was a battle in which the consequences were so vast, so immediate, and so permanent.” And in his Lord Clive he writes: “The work of Clive [who later took his own life in England at only 50 years of age] was, all things considered, as great as that of Alexander.” This is true; for Clive realized that the path of dominion lay open. “It is scarcely hyperbole to say,” he wrote, “that tomorrow the whole Moghul empire is in our power.”15

Recalling what General Fuller has already said about the Bank of England and the manipulation of the National Debt, we may now further appreciate what he says about the growing claims of Mammon and the progress of a Mammonite Colonial Empire:

Yet this victory [at the 1757 Battle of Plassey], on the shifting banks of the Bhagirathi, produced deeper changes still. From the opening of the eighteenth century, the western world had been big with ideas, and the most world-changing was the use of steam as power [also to enhance British sea-power]. Savery, Papin and Newcomen all struggled with the embryo of this monster, which one day was to breathe power over the entire world [which now has also other advanced technologies to deal with]. All that was lacking was gold to fertilize it [like the old alchemist’s dream and delusion of the “maturing of metals”!], and it was Clive who undammed the yellow stream.16

“Howso?”, we may ask.

Quoting the Liberal-Whig historian, Lord Macaulay, General Fuller says:

“As to Clive,” writes Macaulay, “there was no limit to his acquisition but his own moderation. The treasury of Bengal was thrown open to him…. Clive walked between heaps of gold and silver, crowned with rubies and diamonds, and was at liberty to help himself.” India, that great reservoir and sink of precious metals, was thus opened, and from 1757 enormous fortunes were made in the East, to be brought home to England to finance the rising industrial age [and Whig Aristocracy-Oligarchy], and through it to create a new and Titanic world.17

Such was the swollen and swelling “Globalism” or Cosmopolitanism of the Eighteenth Century.

As was the case with earlier plunderers – Alexander, Roman Proconsuls, and Spanish Conquistadores – the candid Fuller then adds:

So now did the English nabobs, merchant princes and adventurers [and their own “Feudalities” of the time] … unthaw the frozen treasure of Hindustan and pour it into England. “It is not too much to say,” writes Brooks Adams, “that the destiny of Europe [sic] hinged upon the conquest of Bengal.” The effect was immediate and miraculous [sic] …. Suddenly all changed [with the rapid development of “machines”] …. “In themselves inventions are passive … waiting for a sufficient store of force to have accumulated to set them working. That store must always take the shape of money, not hoarded, but, in motion.” Further, after 1760, “a complex system of credit sprang up, based on a metallic treasure [which was largely now “pouring” in from India].”18

As another example how a seeming prosperity, as well as a war, was “henceforth founded on unrepayable debt,” General Fuller goes on to say:

So the story lengthens out, profit heaped upon profit. “Possibly since the world began,” writes Brooks Adams, “no investment has ever yielded the profit reaped from the Indian plunder [as the New Reformation English Oligarchy in the Sixteenth Century and afterwards was based on “the Great Pillage” of the Monasteries, and of the Church in general], because for nearly fifty years [until the Early Nineteenth Century] Great Britain stood without competitor.” Thus it came about that out of the field of Plassey [1757] and the victors’ 18 dead there sprouted forth the power of the nineteenth century. Mammon now strode into supremacy to become the unchallenged god of the western world.19

Such was the idol of the increasingly de-Christianized West. Today the apostasy from historic Christianity has gone, unmistakably, even further.

With a portion of bitter cynicism – or at least hard, cold realism – General Fuller concludes with the following words, which should also provoke our further reflectiveness:

Once in the lands of the rising sun western man had sought the Holy Sepulchre. That sun had long set, and now in those spiritually arid regions he found the almighty sovereign. What the Cross had failed to achieve, in a few blood-red years, the trinity of piston, sword, and coin accomplished: the subjection of the East and for a span of nearly 200 years [as of 1955] the economic serfdom of the Oriental world.20

Will such institutions as Halliburton and its own military subsidiary, Kellog, Brown, and Root, also be able to do such things today in Iraq or Afghanistan? And should this be permitted? Ought they be allowed – with their own private military or security forces – to expand their networks into a comparable system of corruption?

To what extent will they have, and maybe even continue to have, “influence without accountability”? And, if not, where are the effective sanctions: clear and enforceable sanctions?

It is now widely known that, down the years, the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States has had its own “contractors,” to include various “front companies” at home and abroad, which are sometimes called “proprietaries” or “asteroids.” Even in their “covert” or “clandestine” activities, however, they had gradually developed a system of regulation and control and accountability. “Black operations” – which deceptively purport to be someone or something other than who or what they truly are – always require even greater supervision and accountability – perhaps, most especially in “black” financial operations! Multiple, insufficiently controlled and disciplined “black” or “false flag” operations can very easily get out of control, and can often be self-sabotaging or mutually destructive.

Standards of moral responsibility and accountability in such matters must therefore remain high, given the weaknesses and vulnerabilities of human nature, and C.I.A. has itself various levels of oversight, to include Congressional Oversight. No one should expect that these forms of moral supervision and control are sufficient, but the culture and traditions of the civilian intelligence community do have ways of honorably “policing” themselves. The self-policing of professionals is one of their distinguishing marks.

However, there is today even less oversight of the “special activities” of the Department of Defense, and, therefore, C.I.A. has been tempted at times to “fold itself under” the more spacious and protecting wings of the Military. And the Military has had its own special temptations to evade certain kinds of accountability concerning the nature and scope of its own “special activities.” But, once again, there is still a traditional military culture of “duty, honor, country” that continues (without romantic sentimentalism) to set just moral limits to warfare.

With the growth of special technologies and “space assets,” however, to include “cyberspace,” and especially so in the undefined and growing “Global War on Terrorism” (“the GWOT”), and in the newly added “War against Tyranny,” the temptation to use “irregular” methods and more “unrestricted warfare” is greater. (And a temptation wouldn’t be a temptation if it weren’t attractive.) Likewise greater is an ingrained inattentiveness and ignorance of consequence – especially the decisive and long-range consequences.

A fortiori is this the case with the even less accountable networks of Private Military Companies, which also create a “command-and-control” nightmare for a uniformed Military Commander in his own assigned Area of Responsibility (AOR), especially in a Combat Zone, where he already has, in addition to “the enemy,” the difficulty of dealing with many dubious Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) – to include groups of Journalists and Lawyers (and other “self-nominating targets”)!

When the United States as a purported and increasingly multicultural nation essentially wants to have – and to sustain – a Global Hegemony and thus a new kind of Imperium, or Quasi-Empire, then these already existing dangers will increase, not only for resistent foreigners, but for U.S. Citizens themselves and their already weakened Constitutional Order. In order to be prudent about the nature and consequences of increasingly incommensurate, cultural waves of non-Western and other kinds of immigration, the United States must not inadvertently – much less deliberately – create a “Surveillance, Counter-Intelligence Police State” in its anxious, sometimes delusive, pursuit of “sufficient security.”

In areas of “ambiguity” – in the “interstices” of law and conflicting jurisdictions – great discipline and self-limitation are required – hence a high standard and an intimate moral culture of honorable accountability. The greater the ambiguity and “gray areas,” the greater the virtue needed!

Such an ethos is against a deceitful “system” of anonymity and impersonality and unaccountability. (And morality is not reducible to legality.)

But, when war and comprehensive “security” are made much more “profitable” and when more and more people develop “vested interests” and “lusts” for such “profits” and for “influence without accountability,” then war and “security services” will become – in the words of Marine General Smedley Butler – even more of a “Racket”! And this must be persistently resisted. Otherwise, there will not just be a growing “seam” between war and criminality; there will grow an increasing “overlap” – indeed, a very ugly “convergence” or “congruence” of war, security, and criminality. And unrestricted war will become unrestricted criminality.

Unable now to deal more extensively, or intensively, with such a large and growing phenomenon of “private military and security services” in this limited essay, I propose, therefore, to conclude with only two further sets of suggestions for our deeper inquiry; and then to consider one revealing example of the manifold missions of one U.S. “private military company,” in the Balkans. This final example is also intended to be a parable, of sorts, for our deeper reflections upon this whole matter of Mercenaries and Finance and the Empire – or Quasi-Empire. These matters must be stripped of all obscuring and deceitful euphemisms and be seen “whole and entire,” as they truly are! No Bullshitsky!

The two suggestions:

1. Look more deeply at the growing “militarization” of both “police forces” and “secret societies,” both at home and abroad – in light of various nations’ own historical practices and cultural traditions of Statecraft and Strategic Intelligence. (China, Great Britain, and Israel are particularly good examples.) Adda Bozeman’s Strategic Intelligence and Statecraft: Selected Essays contains several historical-strategic cultural studies of great worth.21

More specifically, look at NORDEX, the former “KGB Trans-National Corporation” and its current “re-structuring” and evasive mutations and “deployments” in Europe and elsewhere. Look at how the British made strategic use of “Military Masonic Lodges” in their earlier revolution-fomenting penetration of Latin America, especially in and through Brazil (given its strategic location), soon after the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. Look at the Triad Operations and the Yakusa Apparatus in the longer light of Oriental Secret Societies, especially military secret societies.

2. Look at various modern examples of “private military companies” or “networks of multicultural mercenaries” – like Executive Outcomes or Sandline International – and whom they serve (e.g. the oligarchs – or “overlords” – of strategic minerals and key strategic resources); and how they are related to and funded by – even indirectly – various foreign governments, financiers, and intelligence agencies, as well as being involved in the widening covert institutionalization of “Special Operations Forces” (SOF), also in Israel. Look at how official SOF organizations, in Britain and the U.S., for example, allow (without penalty) their “active duty” members to serve for some years with contractors or “mercenaries,” and then return to their former official positions in uniform, along with a fund of “wider experience” and “adventure.”

The case of Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI) in Bosnia is, as follows – and we must remember that MPRI itself helped to write the two main Army Field Manuals concerning “Contractors” and “Contracting Support on the Battlefield”:

In 1997 [after MPRI “successes” in Croatia and Bosnia] the Army determined that it needed guidance on the conduct and regulation of private military companies and directed its Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) to prepare the regulations. So what did TRADOC do? It hired MPRI to develop and write the regulations, of course. The results, approved by TRADOC and the Department of the Army, produced Field Manual (FM) 100-10-2, Contracting Support on the Battlefield, released in April 1999, and FM 100-121, Contractors on the Battlefield, the following September [1999].22

In the further words of Lanning,

Whereas it was said in the nineteenth century that the sun never set on the British Empire, it may be stated that in the twenty-first, the sun never sets on employers of MPRI [established in 1987, in Alexandria, Virginia]. Today, MPRI contractors [also less politely known as “mercenaries”] can be found in every continent of the world with the exception of Antarctica, and that frozen land may very well be a future source of contracts.23

After training “the Croatian National Army” (starting in September 1994), they moved from being “a moderately successful private military firm into a worldwide influence on modern soldiers of fortune.”24

In May 1996, the government of Bosnia hired MPRI “to reorganize, arm, and train its armed forces” and “the contract differed from that with Croatia in that this one [of 1996] specifically contained provisions for MPRI to provide combat training.”25

Now, we shall see how a “private” U.S.-based Military Company helped establish and fortify an Islamic Republic in the heart of Europe:

MPRI and Bosnian officials agreed to a contract amounting to $50 million for the first year with provisions for annual renewals. Another $100 to $300 million was authorized [by whom?] for the purchase of arms and equipment. Although the U.S. State Department had to approve the MPRI portions of the contract and maintain some oversight of the entire operation, the U.S. government did not finance the program. Instead, the money came from a coalition of moderate [sic] Islamic countries, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Brunei, and Malaysia, which hoped that the improved Bosnian army could protect the country’s Muslim majority from its non-Mulsim neighbors …. To introduce the weapons into the Bosnian Army and to train the force, MPRI sent retired U.S. Army Major General William Boice, recently commander of the U.S. 1st Armored Division, and a team of 163 veteran U.S. military personnel.26

U.S. Government-approved, retired U.S. military-mercenaries help establish a better-armed and better-trained, militarized Islamic Republic in the heart of Europe – a Muslim Republic funded by a Coalition of Muslim Countries from afar. What’s wrong with this picture?

How should the Europeans, not only the Americans, respond to such a strategically subversive travesty: a penetration and permeation not only of the strategic threshold of Europe (like the Maghreb), but a further Islamic penetration of the historical heartland of Christendom?

The answer to this question – and our active response – will have great consequence upon the larger flow of migrations – whether from the Maghreb or from Mexico – and also upon the larger cultural and religious struggles we are unmistakably in!

Moreover, with reference to Private Military Companies and their expanding missions:

During the Gulf War in 1991 there was only one contract employee for every hundred uniformed military personnel supporting the conflict. In Operation Iraqi Freedom [which began in March of 2003], the number of contractors has increased to one per every ten soldiers. By mid-2004 the best estimate on the number of private military companies providing direct combat services [sic] to various governments and causes is more than two hundred. There are a dozen or more PMCs [Private Military Companies] in Africa that filled the vacancy left by Executive Outcomes. Several more are based in western European countries. Many more, and some of the most secretive, are based in Russia and other countries once part of the Soviet Union [as well as in Israel and China?]. The vast majority of the private military companies, however, are in the United Kingdom and the United States.27

In the longer light of history, especially the strategic history of the military-merchant-financier British East India Company – with its oligarchic “banker merchants” and “merchant princes and adventurers” and their exercise of increasing “political power” – we may now better understand the likely effects upon the conduct of war of the modern “Private Military Companies,” as a new institution of Mercenaries with a “global reach” and “special technologies” and other “covert assets.” American private military contractors may have even more “reach” (but at what long-range cost?), if they are permitted to have “sub-contractors” from foreign countries like Israel. For, unlike the United States, the Israelis have at their disposal deep knowledge of numerous foreign languages and cultures, and many “linguistic skills,” as well as “interrogation skills.” But, if Israelis are even suspected of being the interrogators of Iraqi Muslims, as at Abu Ghraib prison, for example, the consequences or “blowback” would be very grave for the United States. We must be very attentive to the “farming out” of such matters. We must not be supine or fatalistic, and thus surrender to the view that “the process is irreversible.”

The conduct of war will be greatly affected by the combination of “Special Operations Forces” (SOF) and “Special Technical Operations” (STO) under a variety of new forms of “privatization” or “non-official cover.” These well-financed and “globalized” Private Military Companies will likely have access to advanced and “breakthrough” technologies, and will be more readily disposed than our conventional forces “to exercise them in innovative ways.”

Given the earlier precedents in England – because of the established institutions of the National Debt and the Bank of England and “a complex system of credit” – “war [has been] henceforth founded on unrepayable debt.” The “destinies of nations” and “the frontiers of Empire” are still gravely affected – especially the destinies of dependent “little nations” – by the strategic manipulation of National Debt and of the Debt Bondage of those economically weaker nations or arguably “failing states.”

The combination of modern “banker merchants” and “military adventurer-hucksters” is “a terrible thing to think upon” (in the cheerful words of François Rabelais).

What will be the ultimate loyalties and guiding ethos of such Private Military-Merchant Companies and their foreign “Sub-Contractors” – whether in Iraq or Indonesia or in the restive Southern Hemisphere of Latin America?

In a time of “borderless economies and finance,” how are these new martial-mercantile Feudalities likely to affect the common good of vulnerable societies, who are especially in need of a well-rooted, humane scale of life – not a restless and roaming uprootedness? Whom will these new Overlords serve, and to what extent will these Trans-National Corporate Elites serve the true common good of the United States and provide for the common defense?

And, as always, how does a humane political order regulate and control “the Money Power” and disallow it from being “le pouvoir sur le pouvoir” (“the power above the power”), i.e., from being only superordinate, instead of always subordinate?

The financial and credit question is additionally complicated today by the reality of electronics (“Virtual Money”) and the reality of drugs. Drugs themselves indeed often constitute, not only a currency, but also an access to liquidity – and hence a source of strategic manipulation and “money-laundering,” especially for covert intelligence and military operations.

The spreading phenomenon of the privatization of warfare and “security services” must be understood – and often, not only strictly regulated, but altogether and persistently resisted – especially in light of the lessons that should be learned from earlier Imperial Histories and Economic Colonizations; and also in light of current strategic realities, to include the seemingly reckless, diplomatic and military conduct of the United States. Its foreign “Nation-Breaking” is much more evident than its foreign “Nation-Building,” and not only in Iraq! As distinct from an “Emerging American Imperium,” we may be witnessing, instead, a Submerging American Imperium now making further, even frantic, use of “Private Military Companies” and their “New Feudalities,” both as an imperial “weapon of weakness” and in an act of provocative desperation. For the United States, now often perceived as a “Rogue Superpower,” does increasingly seem to be out of control.

CODA

The Dangerous Moral Aftermath of Promiscuously Applied Irregular Warfare

Almost forty years ago B.H. Liddell Hart, General J.F.C. Fuller’s British colleague, published a second revised edition of his book, Strategy, wherein he had added an entirely new chapter, entitled “Guerrilla War” (Chapter XXIII).28 He sought to understand “particularly the guerrilla and subversive forms of war” and thereby to enhance our “deterrence of subtle forms of aggression,” or “camouflaged war,” which he also called “forms of aggression by erosion.”29

Alluding to Winston Churchill’s short-sighted and promiscuous promotion of irregular warfare behind enemy lines in War War II, and also to “the material damage that the guerrillas produced directly, and indirectly in the course of [enemy] reprisals,” Liddell Hart speaks of how all of this often-provoked (yet always consequential) suffering became, indeed, “a handicap to recovery after liberation.”30 Then, even more profoundly, he adds:

But the heaviest handicap of all, and the most lasting one, was of a moral kind. The armed resistance movement attracted many “bad hats” [i.e., rogues, knaves, dupes, and criminals]. It gave them license to indulge their vices and work off [i.e., avenge] their grudges under the cloak of patriotism…. Worse still was its wider effect on the younger generation as a whole. It taught them to defy authority and break the rules [in their “black operations” or “unrestricted warfare”] of civic morality in the fight against the occupying forces [whether German, Japanese, or, today, Israeli occupation forces]. This left a disrespect for “law and order” that inevitably continued after the invaders had gone. Violence [to include vandalism and terrorism] takes much deeper root in irregular warfare than it does in regular warfare. In the latter it is counteracted by obedience to constituted authority, whereas the former [more lawless, irregular warfare] makes a virtue of defying authority and violating rules [hence “limits”]. It becomes very difficult to rebuild a country, and a stable state, on a foundation undermined by such experience.31

Even moreso is this the case today when “new feudalisms,” mercenary warfare and strategically-organized “private military companies” are promiscuously set loose to fight an increasingly undefined “global war on terrorism.” For, it unmistakably fosters “the privatization of lawlessness” and soon gets further out of control.

Moreover, these new indirect forms of warfare – and the asymmetrical (irregular) cultural and strategic resistance against them – often have, despite the secular appearances, very deep and very tenacious religious roots, to include Hebraic-Islamic roots.

—FINIS—

© 2006 Robert Hickson

1Robert Hickson, “Setting Just Limits to New Methods of Warfare” in Neo-Conned! – Just War Principles (Vienna, Virginia: IHS Press – Light in the Darkness Publications, 2005), pp. 331-343 (Chapter 18).

2See the transcript of the 9-10 October Conference at Middlebury College, Middlebury, Vermont (http://www.wws.princeton.edu/ppns/conferences/reports/privtranscript.pdf); the Conference, entitled “The Privatization of American National Security” was held at the Rohatyn Center for International Affairs. Immediately after his above-quoted words, Feaver said: “A number of folks have expressed the concern that this makes military force [as in the case of the East India Company] too usable a tool [of Empire]. That was precisely the issue raised by the rescinding of the draft [in 1973]” (my emphasis added). Correlative with this “rescinding of the draft” was the creation of the “all-volunteer force” in the United States.

3William E. Odom and Robert Dujarric, America’s Inadvertent Empire (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2004). These thoughtful and manifoldly discerning authors also give much weight to the importance of a Constitutional Order – for them a Liberal Order – which always requires a preceding agreement and what the authors call a “Great Compromise” among the given polity’s component Elites, which would otherwise be able to break with relative impunity the prevailing rules of society.

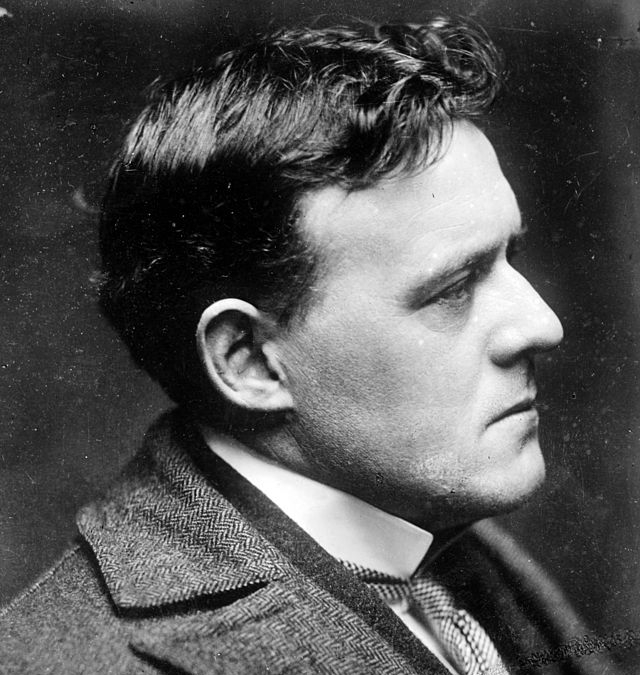

4Hilaire Belloc, Esto Perpetua: Algerian Studies and Impressions (New York: AMS Press, 1969 – first published in London, in 1906), pp. 25-28, and 36-37 – my emphasis added.

5See Michael Lee Lanning, Mercenaries: Soldiers of Fortune, from Ancient Greece to Today’s Private Military Companies (New York: Ballantine Books, 2005). Lanning’s book is a very useful survey of the phenomenon, despite some important gaps in its treatment, especially with respect to foreign strategic cultures (e.g., Russia, Israel, China, Ancient Persia and the Islamic World). He also has a useful Bibliography, pp. 26-272, and some valuable Appendixes.

6Ibid., p. 1.

7Ibid., p. 214 – my emphasis added.

8Ibid., p. 222 – my emphasis added.

9J.F.C. Fuller, A Military History of the Western World – Volume II (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1955), p. 153-154 – my emphasis added.

10Ibid., p. 154 – my emphasis added.

11Ibid., pp. 154-155 – my emphasis added.

12Ibid., p. 217.

13Ibid., p. 218.

14Ibid., p. 155 – my emphasis added.

15Ibid., p. 240 – my emphasis added.

16Ibid. – my emphasis added.

17Ibid., p. 241 – my emphasis added.

18Ibid. – my emphasis added. – Between 1756 and 1815, the National Debt increased from 74.58 Million Pounds to 861 Million Pounds!

19Ibid., p. 242 – my emphasis added.

20Ibid. – my emphasis added.

21(Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 1992). See, especially, her essay on “Statecraft and Intelligence in the Non-Western World” (pages 180-212).

22Michael Lee Lanning, Mercenaries, p. 203 – my emphasis added.

23Ibid., p. 198.

24Ibid., pp. 199-200.

25Ibid., p. 200 – my emphasis added.

26Ibid. – my emphasis added.

27Ibid., p. 206 – my emphasis added.

28B.H. Liddell Hart, Strategy (New York: Penguin – A Meridian Book, 1967), “Guerrilla War,” pp. 361-370.

29Ibid., pp. 361, 370, 363.

30Ibid., pp. 368-369.

31Ibid., p. 369 – my emphasis added.