Note: this essay has first been published at LifeSiteNews.com and is re-printed here with kind permission.

by Dr. Maike Hickson

Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò has recently written a preface for a book, Gratitude, Contemplation, and the Sacramental Worth of Catholic Literature, a collection of essays written by my husband Dr. Robert Hickson over the course of several decades. Being a distillation of his life work, this new book aims at presenting to the readers a whole set of inspiring books – most of them Catholic – that can help us restore a Catholic memory. That is to say, these books can help us revive a sense of Catholicity that comes to us from time periods and regions where the Catholic faith was an integral part of the state and society, from a lived faith.

We are very grateful to Archbishop Viganò for his preface, which highlights the importance of culture – and importantly, literature – for the revival of Christianity, and therefore we decided to publish it here (see full text below). His comments aim at turning our minds to the future, preparing the ground for a time where Christ again will reign in the heart and minds of man. His preface is therefore a sort of manifesto of faith and hope, and a wonderful instruction for us on how to go about preparing the ground for Christ.

The Italian prelate and courageous defender of the faith points to the importance of having a memory of our Catholic culture. “Memory,” he writes, “is a fundamental element of a people’s identity, civilization and culture: a society without memory, whose patrimony consists solely of a present without a past, is condemned to have no future. It is alarming that this loss of collective memory affects not only Christian nations but also seriously afflicts the Catholic Church herself and, consequently, Catholics.” The lack of culture among Catholics today, he adds, is “not the result of chance, but of systematic work on the part of those who, as enemies of the True, Good and Beautiful, must erase any ray of these divine attributes from even the most marginal aspects of social life, from our idioms, from memories of our childhood and from the stories of our grandparents.”

Describing this cultural tabula rasa that has taken place among Catholics, Archbishop Viganò goes on to say that “Reading the pages of Dante, Manzoni or one of the great Christian writers of the past, many Catholics can no longer grasp the moral and transcendent sense of a culture that is no longer their common heritage, a jealously guarded legacy, the deep root of a robust plant full of fruit.”

On the contrary, he explains, “in its place we have a bundle of the confused rubbish of the myths of the Revolution, the dusty Masonic ideological repertoire, and the iconography of a supposed freedom won by the guillotine, along with the persecution of the Church, the martyrdom of Catholics in Mexico and Spain, the end of the tyranny of Kings and Popes and the triumph of bankers and usurers.”

Archbishop Viganò clearly shows us that he understands the concept of a “cultural revolution” as developed by the Communist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, who aimed at winning the minds of the people by influencing and dominating their culture.

This cultural – and with it spiritual – empoverishment among Catholics, according to the prelate, “has found significant encouragement also among those who, within the Catholic Church, have erased 2,000 years of the inestimable patrimony of faith, spirituality and art, beginning with a wretched sense of inferiority instilled in the faithful even by the hierarchy since Vatican II.” It was the very hierarchy of the Church – together with many simpler clergymen – who helped promote such a devastation of the art within the realm of the Catholic Church. Let us only think of the modern churches, altars, and of modern church music!

With powerful words, Archbishop Viganò describes how this destruction is ultimately aimed at God Himself: “Certainly, behind this induced amnesia, there is a Trinitarian heresy. And where the Deceiver lurks, the eternal Truth of God must be obscured in order to make room for the lie, the betrayal of reality, the denial of the past.” In light of this analysis, it nearly seems to be a counter-revolutionary act to revive Catholic literature, Catholic music, Catholic architecture.

Explains the prelate: “Rediscovering memory, even in literature, is a meritorious and necessary work for the restoration of Christianity, a restoration that is needed today more than ever if we want to entrust to our children a legacy to be preserved and handed down as a tangible sign of God’s intervention in the history of the human race.”

It is in this context that he kindly mentions the “meritorious work” of this new book, praising its “noble purpose of restoring Catholic memory, bringing it back to its ancient splendor, that is, the substance of a harmonious and organic past that has grown and still lives today.” He adds that “Robert Hickson rightly shows us, in the restoration of memory, the way to rediscover the shared faith that shapes the traits of a shared Catholic culture.”

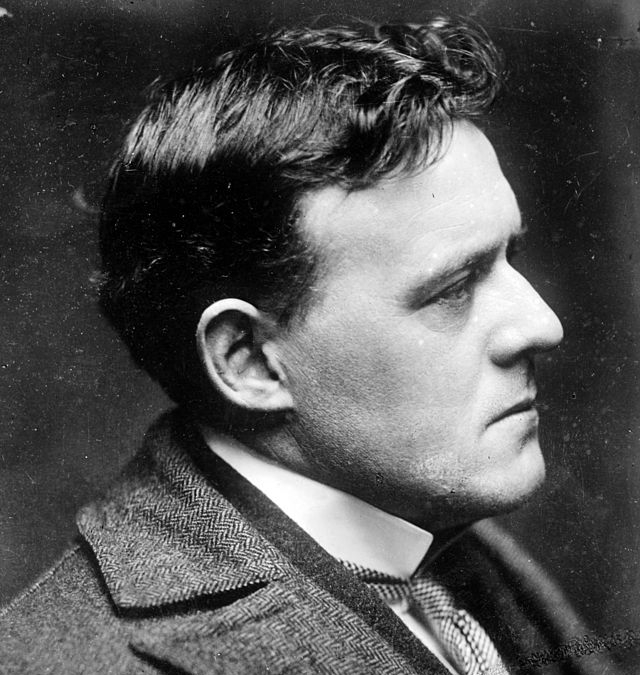

Dr. Hickson’s new book was published last month and contains 25 essays on many different Catholic authors, such as Hilaire Belloc, G.K. Chesterton, Maurice Baring, Evelyn Waugh, Josef Pieper, George Bernanos, Ernest Psichari, Father John Hardon, S.J., L. Brent Bozell Jr., and, last but not least, the Orthodox Christian authors Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. The themes of this book are war and peace, justice, the Catholic vow, saints, friendship, chivalry, martyrdom and sacrifice, just to name a few. The essays of the book were written from 1982 until 2017, the first being an essay where Hickson developed the concept of “sacramental literature” and the importance of “restoring a Catholic memory.” Anthony S. Fraser, the son of the famous Catholic convert and traditionalist, Hamish Fraser, kindly had edited the essays for his friend, before he so suddenly died on August 28, 2014, the Feast of St. Augustine of Hippo. May his soul rest in peace. We thank you, Tony!

Here is the full preface written by Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò:

Memory is a fundamental element of a people’s identity, civilization and culture: a society without memory, whose patrimony consists solely of a present without a past, is condemned to have no future. It is alarming that this loss of collective memory affects not only Christian nations, but also seriously afflicts the Catholic Church herself and, consequently, Catholics.

This amnesia affects all social classes and is not the result of chance, but of systematic work on the part of those who, as enemies of the True, Good and Beautiful, must erase any ray of these divine attributes from even the most marginal aspects of social life, from our idioms, from memories of our childhood and from the stories of our grandparents. The Orwellian action of artificially remodeling the past has become commonplace in the contemporary world, to the point that a class of high school students are unable to recognize an altarpiece depicting a scene from the life of Christ or a bas-relief with one of the most revered saints of the past. Dr. Robert Hickson calls this inability “deficiency of dogmatic understanding”, “Catholic illiteracy of pestilential proportions”.

Tabula rasa: millions of souls who only twenty or thirty years ago would have immediately identified the Baptism of the Lord in the Jordan or Saint Jerome or Saint Mary Magdalene are capable of seeing only two men along a river, an old man with a lion and a woman with a vase. Reading the pages of Dante, Manzoni or one of the great Christian writers of the past, many Catholics can no longer grasp the moral and transcendent sense of a culture that is no longer their common heritage, a jealously guarded legacy, the deep root of a robust plant full of fruit.

In its place we have a bundle of the confused rubbish of the myths of the Revolution, the dusty Masonic ideological repertoire, and the iconography of a supposed freedom won by the guillotine, along with the persecution of the Church, the martyrdom of Catholics in Mexico and Spain, the end of the tyranny of Kings and Popes and the triumph of bankers and usurers. A lineage of kings, saints, and heroes is ignored by its heirs, who stoop to boasting about their ancestors who were criminals, usurpers, and seditious traitors: never has falsification reached the point of such incomprehensible perversion, and it is evident that the desire to artificially create such ancestry is the necessary premise for the barbarization of the offspring, which is now practically accomplished.

We must also recognize that this removal has found significant encouragement also among those who, within the Catholic Church, have erased two thousand years of the inestimable patrimony of faith, spirituality and art, beginning with a wretched sense of inferiority instilled in the faithful even by the Hierarchy since Vatican II. The ancient apostolic liturgy, on which centuries of poetic compositions, mosaics, frescoes, paintings, sculptures, chiseled vases, illuminated chorales, embroidered vestments, plainchants and polyphony have been shaped, has been proscribed. In its place we now have a squalid rite without roots, born from the pen of conspirators dipped in the inkwell of Protestantism; music that is no longer sacred but profane; tasteless liturgical vestments and sacred vessels made of common material. And as a grey counterpoint to the hymns of St. Ambrose and St. Thomas, we now have poor paraphrases without metrics and without soul, grotesque paintings and disturbing sculptures. The removal of the admirable writings of the Fathers of the Church, the works of the mystics, the erudite dissertations of theologians and philosophers and, in the final analysis, of Sacred Scripture itself – whose divine inspiration is sometimes denied, sacrilegiously affirming that it is merely of human origin – have all constituted necessary steps of being able to boast of the credit of worldly novelties, which before those monuments of human ingenuity enlightened by Grace appear as miserable forgeries.

This absence of beauty is the necessary counterpart to an absence of holiness, for where the Lord of all things is forgotten and banished, not even the appearance of Beauty survives. It is not only Beauty that has been banished: Catholic Truth has been banished along with it, in all its crystalline splendor, in all its dazzling consistency, in all its irrepressible capacity to permeate every sphere of civilized living. Because the Truth is eternal, immutable and divisive: it existed yesterday, it exists today and it will exist tomorrow, as eternal and immutable and divisive as the Word of God.

Certainly, behind this induced amnesia, there is a Trinitarian heresy. And where the Deceiver lurks, the eternal Truth of God must be obscured in order to make room for the lie, the betrayal of reality, the denial of the past. In a forgery that is truly criminal forgery, even the very custodians of the depositum fidei ask forgiveness from the world for sins never committed by our fathers – in the name of God, Religion or the Fatherland – supporting the widest and most articulated historical forgery carried out by the enemies of God. And this betrays not only the ignorance of History which is already culpable, but also culpable bad faith and the malicious will to deceive the simple ones.

Rediscovering memory, even in literature, is a meritorious and necessary work for the restoration of Christianity, a restoration that is needed today more than ever if we want to entrust to our children a legacy to be preserved and handed down as a tangible sign of God’s intervention in the history of the human race: how much Providence has accomplished over the centuries – and that art has immortalized by depicting miracles, the victories of the Christians over the Turk, sovereigns kneeling at the feet of the Virgin, patron saints of famous universities and prosperous corporations – can be renewed today and especially tomorrow, only if we can rediscover our past and understand it in the light of the mystery of the Redemption.

This book proposes the noble purpose of restoring Catholic memory, bringing it back to its ancient splendor, that is, the substance of a harmonious and organic past that has grown and still lives today, just as the hereditary traits of a child are found developed in the adult man, or as the vital principle of the seed is found in the sap of the tree and in the pulp of the fruit. Robert Hickson rightly shows us, in the restoration of memory, the way to rediscover the shared faith that shapes the traits of a shared Catholic culture.

In this sense it is significant – I would say extremely appropriate, even if only by analogy – to have also included Christian literature among the Sacramentals, applying to it the same as action as that of blessed water, the glow of the candles, the ringing of bells, the liturgical chant: the invocation of the Virgin in the thirty-third canto of Dante’s Paradiso, the dialogue of Cardinal Borromeo with the Innominato, and a passage by Chesterton all make Catholic truths present in our minds and, in some way, they realize what they mean and can influence the spiritual life, expanding and completing it. Because of this mystery of God’s unfathomable mercy we are touched in our souls, moved to tears, inspired by Good, spurred to conversion. But this is also what happens when we contemplate an altarpiece or listen to a composition of sacred music, in which a ray of divine perfection bursts into the greyness of everyday life and shows us the splendor of the Kingdom that awaits us.

The author writes: “We are called to the commitment to recover the life and full memory of the Body of Christ, even if in our eyes we cannot do much to rebuild that Body”. But the Lord does not ask us to perform miracles: He invites us to make them possible, to create the conditions in our souls and in our social bodies so that the wonders of divine omnipotence may be manifested. To open ourselves to the past, to the memory of God’s great actions in history, is an essential condition for making it possible for us to become aware of our identity and our destiny today so that we may restore the Kingdom of Christ tomorrow.

+ Carlo Maria Viganò

Titular Archbishop of Ulpiana

Apostolic Nuncio

28 August 2020

Saint Augustine

Bishop, Confessor, and Doctor of the Church