Dr. Robert Hickson

28 January 2006

Saint Thomas Aquinas

Saint Peter Nolasco

(Author’s Note of 30 November 2021: Evelyn Waugh’s heart-felt text was first published in 1935, and dedicated to Father Martin D’Arcy, S.J. of Campion Hall, Oxford University. This current essay was first published in 2006 and will be published here once more in honor of Saint Edmund Campion, for his feast day on December 1.)

The scope and depth of Evelyn Waugh’s grateful and manly book, Edmund Campion, will, when receptively savored, illuminate and fortify those of the Catholic Faith today amidst their own special composite of challenges. For, as Waugh wrote in 1935: “The Church has vast boundaries to defend, and each generation finds itself called to service upon a different front.”[1]

In the longer light of history — informed by an attendant view of supernatural Grace and the other fundamental Christian Mysteries — Waugh shows in his deftly written 1935 book, only five years after his grateful reception into the Catholic Church, how the life of Edmund Campion bore intimate resemblances to the life and love of Christ, especially at the end. This book, moreover, will help us to see more clearly how we, too, must confront the mystery of iniquity today, to include the phenomenon of pervasive perfidy, which is sometimes so intrusive; and to do so without rash unwisdom or impetuous anger, but, rather, with high prudence and deeply abiding, intimate trust in the Providential Mercy of God rooted in the hearts of Christ and His Immaculate Mother, who will faithfully love us, and whom we must faithfully love, to the end. The greater the evil that God allows, the greater the good He intends to bring out of it. To what extent will we promptly and wholeheartedly — and perseveringly — collaborate with that generous Divine Intention? Edmund Campion did, knowing from the Council of Trent full well that the Grace of Final Perseverance itself is a great gift, a “Magnum Donum.”

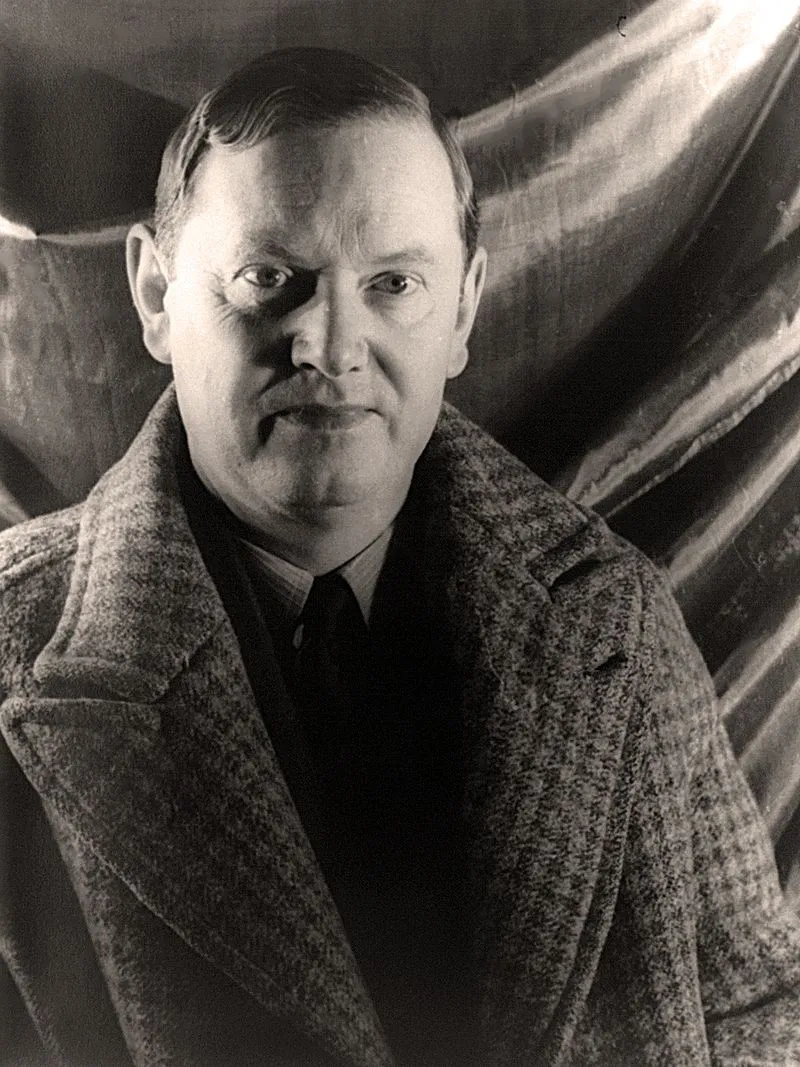

One purpose of this essay is to give honor to Evelyn Waugh, a sometimes difficult man, but a great defender of the Faith in the Modern World, which he often so rumbustiously and wholeheartedly detested. One of his lovable characters, Scott-King (“Scottie”), the classical master at Grandchester Public School in England conclusively said to his progressive Headmaster: “I think it would be very wicked indeed to do anything to fit a boy for the modern world.”[2] Dying on Easter Sunday 1966 in his home, shortly after the Jesuit Father Philip Caraman celebrated the Traditional Latin Mass in a nearby Chapel, Waugh also suffered much from what he saw happening at, and shortly after, the Second Vatican Council — especially in the Liturgy and from the duplicity and perfidious manipulations of the clergy, especially Cardinal Heenan in England.[3] Like Edmund Campion, in part, Evelyn Waugh had his own “bitter trial” at the end — but so did Our Lord.

With his characteristic modesty, G.K. Chesterton once compared his entrance into the Catholic Church (in 1922, only eight years before Waugh) with the entrance into a Gothic Church. Inside a Gothic Church it is even more spacious than from without — i.e., when it is only seen from the outside, from different, but incomplete, perspectives. So, too, with the Catholic Faith and the Catholic Church. From within the Church the spaciousness of the Faith is even greater (and more intimate) than when only seen from the outside. The life and times of Saint Edmund Campion (1540-1581) are also seen with greater intimacy and spaciousness when seen from the inside of a beautiful book. This is to say, in and through the language and varied tones of Evelyn Waugh’s Edmund Campion.

Here, for example, is what Waugh wrote about the mystery of the character of Edmund Campion, who, in his short life and increasing witness to the truth, “suddenly emerges as a hero,” even though, from the beginning, it was vividly perceptible that “He was not a reserved man; he loved argument; ideas for him demanded communication”:[4]

It was an age [the Sixteenth Century] replete with examples of astounding physical courage. Judged by the exploits of the great adventurers of his time, the sea-dogs and explorers, Campion’s brief achievement [especially from his return to England in late June 1580 until his truculent martyrdom on 1 December 1581] may appear modest enough; but these were tough men, ruthlessly hardened by upbringing, gross in their recreations. Campion stands out from even his most gallant and chivalrous contemporaries, from [Sir] Philip Sidney and Don John of Austria [hero of Lepanto], NOT as they stand above Hawkins [the English buccaneer-pirate] and Stukeley by a finer human temper, but by the supernatural grace that was in him. That the gentle scholar, trained all his life for the pulpit and the lecture room, was able at the word of command [in March 1580] to step straight into a world of violence, and acquit himself nobly; that the man capable of strenuous heroism of that last year and a half [June 1580-December 1581], was able, without any complaint, to pursue the sombre routine of a pedagogue [in Prague and Brunn — in both Hussite and Lutheran Bohemia and Moravia] and contemplate a lifetime so employed — there lies the mystery which sets Campion’s triumph apart from the ordinary achievements of human strength; a mystery whose solution lies in the busy, uneventful years at Brunn and Prague [six years], in the profound and accurate piety of the Jesuit rule [hence “the precise discipline of the Ignatian Exercises”].[5]

Edmund Campion possessed a combination of very special qualities which could encourage the Catholics of England “to whom the Jesuits were being sent” and who, in truth, were “guilty of no crime except adherence to the traditional faith of their country”[6] — the Faith of Saint Augustine of Canterbury, Saint Thomas à Becket of Canterbury, and King Saint Edward the Confessor or Saint Thomas More. Under these conditions of life, “always vexatious, often utterly disastrous” the Catholics of Sixteenth-Century England suffered, and:

They were conditions, which, in the natural course, could only produce despair, and it depended upon their individual temperaments whether, in desperation, they had recourse to apostasy or conspiracy. It was the work of the missionaries, and most particularly of Campion, to present by their own example a third supernatural solution. They came with gaiety among a people where hope was dead. The past held only regret, and the future apprehension; they brought with them, besides their priestly dignity and indestructible creed, an entirely new spirit of which Campion is the type: the chivalry of Lepanto and the poetry of La Mancha, light, tender, generous and ardent.[7]

Always himself rooted in reality, Waugh then adds:

After him [Edmund Campion] there still were apostates and there were conspirators; there were still bitter old reactionaries, brooding alone in their impoverished manors over the injustice they had suffered [and perhaps without “forgiveness from the heart”], grumbling at the Queen’s plebeian advisers, observing the forms of the old Church in protest against the crazy, fashionable Calvinism; these survived, sterile and lonely, for theirs was not the temper of Campion’s generation who — not the fine flower only, but the root and stem of English Catholicism — surrendered themselves to their destiny without calculation or reserve; for whom the honorable pleasures and occupations of an earlier age were forbidden; whose choice lay between the ordered, respectable life of their ancestors and the faith which had sanctified it; who followed holiness though it led them through bitter ways to poverty, disgrace, exile, imprisonment and death; who followed it gaily.[8]

How did Campion become a Jesuit? How did it come to pass that, ordained by the Bishop of Prague, Father Campion, S.J., celebrated his first Mass on the Feast of the Nativity of Our Lady, on 8 September 1578 — slightly more than three years before his blood witness for the Faith, at Tyburn, in London, England? Waugh’s vivid and nuanced narrative will lead us to these deeper understandings — and some other insights, as well, about the implications of the Faith. For, the Lord’s last words to His disciples before His Ascension were: “and you shall be witnesses [Greek, “MARTYRES“] for me in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and even to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

In his own narrative of a later martyr for Christ, Waugh’s vivifying style has that “special quality” and “humbler role” of which Lactantius himself spoke in Waugh’s later Historical Novel, Helena (1950). In the later Third Century A.D., Lactantius was speaking of the earlier Christian martyrs of Britain and the recent martyrs of Thrace; he was speaking to Helena, before she became a Christian, and to her companion, Minervina (a sentimental — and somewhat brainless — Gnostic Sympathizer!). Lactantius in his modesty admits that he himself lacked what was needed to face the test of martyrdom, which is why he did not “stay at home in Nicomedia” (in Asia Minor), but fled the Diocletian Persecutions there. In Lactantius’ humble words about the mystery and abiding power of literary style, we also hear the deeper heart of Waugh:

“It needs a special quality to be a martyr — just as it needs a special quality to be a writer. Mine is the humbler rôle, but one must not think it quite valueless. One might combine two proverbs and say: ‘Art is long and will prevail.’ You see it is equally possible to give the right form to the wrong thing, and the wrong form to the right thing. Suppose that in the years to come [for example, in the time of Voltaire or Edward Gibbon], when the Church’s troubles seem to be over, there should come an apostate of my own trade, a false historian, with the mind of Cicero or Tacitus and the soul of an animal,” and he nodded towards the gibbon who fretted his golden chain and chattered for his fruit.” A man like that [who would “sap a solemn Creed with a solemn sneer,” said a poet] might make it his business to write down the martyrs and excuse the persecutors. He might be refuted again and again [with the true evidence and truthful counter-argument] but what he wrote would remain in people’s minds when the refutations were quite forgotten. That is what style does — it has the Egyptian secret of the embalmers. It is not to be despised.”[9]

Unlike the mocking tones and diction and syntax of Edward Gibbon, the gift of Evelyn Waugh’s style in his narrative of a later English martyr — “Pater Edmundus Campianus, Martyr” — gives the right form to the right thing. He uses language, not to conceal, but to reveal reality. That is to say, both the exterior, and the interior, life of Campion.

As we consider the preparation, formation, and full fructification of this gracious and much-beloved Jesuit priest, we should remember that, at the time of Father Campion’s return on “the English mission” as a Catholic priest, there was not yet an English Province of the Society of Jesus. Nor were there any Catholic bishops then in England who were not in prison. The other English Catholic bishops — like the elderly and failing Bishop Goldwell of Saint Asalph — were in exile. Moreover, after Campion was received as a novice in the Society of Jesus in late April 1573, he was assigned to the Austrian Province of the Jesuits for “the Bohemian apostolate” (which included Moravia, as well). The recently elected new General of the Society of Jesus — the Fleming, Mercurianus — approved of this assignment, as well as his later mission to England.[10] But, only three years after Campion’s martyrdom on the gibbet at Tyburn, the new Jesuit General Aquaviva was to write that “to send missionaries in order to give edification by their patience under torture might injure many Catholics and do no good to souls.”[11] The practical wisdom of those missions themselves, as well as the proper methods to be employed in the worsening circumstances in England, would remain a keenly disputed issue, even for those of deep faith who kept as a priority a supernatural criterion and the salvation of souls (salus animarum).

What would today’s laxer, or more tolerant, “Ecumenists” say — those who would inclusively promote, not the conversion of Protestants, but the convergence with Protestants (to include the increasingly innovative and syncretistic Anglicans of modern England)?

Even though Campion, along with Father Alexander Briant and Father Ralph Sherwin and thirty-seven others, was formally canonized on 25 October 1970, how would most “updated” Catholics today likely look upon those intransigent “Recusants” of Elizabethan England who refused to compromise with the eclectic and apostate “Elizabethan Settlement,” as it is euphemistically called? This is an important question, too, for us to reflect upon: to clarify our mind and principles, and to decide. We, too, must be prepared for the test — for the spiritual and moral combat of martyrdom. But, it is hard to pass the test when the test keeps changing. It is all too easy for our human weakness and sloth to say, instead: “If you can’t pass the test, change the test!” Especially, if it is a demanding test. Edmund Campion himself was often offered, as we shall see, comfortable preferments, even by the Queen herself, “would he but apostatize”!

In 1959, thirteen years after his new “Preface to the American Edition” of Edmund Campion, Waugh wrote a new Preface to his second, revised edition of Brideshead Revisited (1945), where he was very explicit about the main purpose of his historical novel. He said: “Its theme — the operation of divine grace on a group of diverse but closely connected characters — was perhaps presumptuously large, but I make no apology for it.”[12] This matter of Grace was so important to him. He knew that Nature was not enough. Certainly not our Fallen Nature, wounded, concupiscent, and intellectually darkened.

In his short 1946 “Preface to the American Edition” of Edmund Campion — the edition without the original 1935 footnotes and bibliography — Waugh also very explicitly says, concerning his narrative, that “It should be read as a simple, perfectly true story of heroism and holiness.”[13]

Emphasizing that “the facts are not in dispute,” he adds:

We [in 1946] have come much nearer to Campion since Simpson’s day [the late Nineteenth Century]. He wrote[14] [1861-2, 1866, 1896] in the flood-tide of toleration, when Elizabeth’s persecution seemed as remote as Diocletian’s. We know now that his age was a brief truce in the unending war.[15]

This theme of the permanent combat was reinforced four years later in his especially beautiful, already quoted, historical novel on the mother of Constantine, Saint Helena, entitled simply Helena (1950). Reflecting upon those other late-comers to Christ, the Three Magi, with whom she humbly identified, Helena says the following — in a passage of the novel just before she is shown to discover the True Cross:

“Like me,” she said, “you were late in coming [“to the truth”, “to Christ”] …. How laboriously you came, taking sights and calculating, where the shepherds had run barefoot [to the Manger]! …. You came to the final stage of your pilgrimage …. What did you do? You stopped to call on King Herod. Deadly exchange of compliments in which there began that unended war of mobs and magistrates against the innocent!”[16]

Christ Himself was being hunted at His birth. Like the impending Slaughter of the Innocents (“Flores Martyrum” — Prudentius) and the later, manipulated mob who preferred Barabbas, so, too, Evelyn Waugh saw what was happening again in that “unending war,” and not only in Mexico:

We have seen the Church driven underground in one country after another. The martyrdom of Father Pro [of the Society of Jesus] in Mexico re-enacted Campion’s. In fragments and whispers we get news of other saints in the prison camps of Eastern and South Eastern Europe, of cruelty and degradation more frightful than anything in Tudor England and of the same pure light [undiluted — like all purity] shining in the darkness, uncomprehended. The hunted, trapped, murdered priest is amongst us again and the voice of Campion comes to us across the centuries as though he were walking at our side.“[17]

Waugh presents a lucid fourfold structure to his book, the four sections being entitled, respectively: The Scholar; The Priest; The Hero; The Martyr. He adds an Appendix, Father Campion’s original threefold Challenge (written in English, not Latin), to Queen Elizabeth’s Lords of the Privy Council, the Doctors and Masters of Oxford and Cambridge, and the Ecclesiastical and Civil Lawyers of the Realm of England. In this challenge — called “Campion’s Brag” by his adversaries — Campion says: “Hereby I have taken upon me a special kind of warfare under the banner of obedience, and eke [also] resigned all my interest or possibilitie of wealth, honour, pleasure, and other worldlie felicitie.”[18]

Campion’s Challenge is an Open Letter which was written spontaneously in July of 1580, by hand, in half an hour, at a village outside London (Hoxton), and at the request of his colleague, Mr. Thomas Pounde, for the purpose of clarifying his true spiritual mission, should he be captured, to those who purportedly suspected him of treason. It concludes with these memorable and still inspiring words of fervor and Faith; knowing very well “upon what substantial grounds our Catholike Faith is builded”:

Hearken to those who would spend the best blood in their bodies for your salvation. Many innocent hands are lifted up to heaven for you daily by those English students [in Douai, of Flanders, in Rheims, and in Rome], whose posteritie shall never die, which beyond seas [in exile], gathering virtue and sufficient knowledge for the purpose [to secure your salvation], are determined never to give you over, but either to win you heaven, or to die upon your pikes. And touching our Societie [the Society of Jesus], be it known to you that we have made a league — all the Jesuits in the world, whose succession and multitude must overreach all the practices of England — cheerfully [with hilaritas mentis] to carry the cross you shall lay upon us, and never to despair your recovery [return to the Faith, conversion unto salvation], while we have a man left to enjoy your Tyburn, or to be racked [by that instrument of pain which hideously later stretched his own limbs apart] with your torments, or consumed with your prisons [the Tower of London]. The expense is reckoned, the enterprise is begun; it is of God, it cannot be withstood. So the Faith was planted: so it must be restored.[19]

Reflecting upon the mysterious and very consequential decision which had been made ten years earlier (in 1570) by the sainted Dominican Pope Pius V, namely, to promulgate on Corpus Christi Day (25 May 1570) the Bull of Elizabeth’s Excommunication and Deposition (Regnans in Excelsis), Evelyn Waugh posed an important question, and with great humility:

Had he [Pope Pius V], perhaps, in those withdrawn, exalted hours before his crucifix, learned something that was hidden from the statesmen of his time and the succeeding generations of historians [who acutely criticized him for his act]; [had he] seen through and beyond the present and the immediate future [e.g., the October 1571 Battle of Lepanto!]; [had he] understood that there was no easy way of reconciliation, but that it was only through blood and hatred and derision that the faith was one day to return to England?[20]

Waugh shows a heart and a humility for this great Dominican Pope despite the manifold, “learned and prudent” criticisms against his Bull of Excommunication and Deposition. Waugh, then says, once again with a supernatural perspective:

It is possible that one of his more worldly predecessors [as Pope] might have acted differently, or at another season, but it was the pride and slight embarrassment of the Church that, as has happened from time to time in her history, the See of Peter was at this moment occupied by a Saint.[21]

Moreover,

His contemporaries and the vast majority of subsequent historians regarded the Pope’s action as ill-judged. It has been represented as a gesture of mediaevalism, futile in an age of new, vigorous nationalism, and its author as an ineffectual and deluded champion [like a Don Quixote], stumbling through the mists, in the ill-fitting, antiquated armour of Gregory [VII] and Innocent [III]; a disastrous figure, provoking instead of a few buffets for Sancho Panza the bloody ruin of English Catholicism.[22]

Waugh’s own artfully ironic description of Saint Pius V’s scoffers shows the depth of his own vision and Faith; and he truly tries to understand the Pope’s deeper reasons and motives:

Pius contemplated only the abiding, abstract principles that lay behind the phantasmagoric changes of human affairs. He prayed earnestly about the situation in England, and saw it with complete clarity; it was a question [a quaestio disputata] that admitted of no doubt whatever. Elizabeth was illegitimate by birth, she had violated her [Catholic] coronation oath, deposed her [Catholic] bishops, issued a heretical Prayer Book and forbidden her subjects the comfort of the sacraments. No honourable Catholic could be expected to obey her.[23]

Indeed, Edmund Campion’s own final words of his threefold “Challenge” (“Brag”) ten years later intimately hoped for an eventual and full reconciliation — but only sub gratia — in Beatitude. With eloquence and warm-heartedness he said:

If these my offers [to be allowed an open, public Disputation about the Faith] be refused, and my endeavors can take no place, and I, having run thousands of miles to do you good [unto your salvation], shall be rewarded with rigour [mortal punishment], I have no more to say but to recommend [entrust] your case and mine to Almightie God, the Searcher of Hearts [Scrutator Cordium], who send us His grace, and set us at accord before the day of payment [the Final Judgment], to the end we may at last be friends in heaven, when all injuries shall be forgotten.[24]

Before first introducing us to Edmund Campion as a young and developing scholar(twenty-six years old), who first met Queen Elizabeth on 3 September 1566 when she was only thirty-three years of age and on her first visit to Oxford University, Waugh begins his book with an unmistakable shock. He depicts Elizabeth in her last illness, a terrible thing to think upon, showing her increasingly withdrawn into silence and sadness, for nearly two weeks in Mid-March 1603, until she lapsed into a final stupor and death, after having sunk more and more into melancholy and muteness and the terrible isolation of the human soul, “where she died without speaking,” “sane and despairing.”[25] It is a stark depiction, indeed. “In these circumstances the Tudor Dynasty came to an end,” Waugh quietly comments, as if he were also implying a parable as well as a warning. For it was that same Tudor Dynasty “which in three generations had changed the aspect and temper of England.”[26]

That is to say, in 1603, almost twenty-two years after Father Campion’s own blood-witness for the Faith, Catholicism in England was fading. It was no longer part of the public order and leadership of the realm. Indeed, says Waugh, that three-generation Tudor Dynasty

Left a new aristocracy, a new religion, a new system of government; the generation was already [even in 1603] in its childhood that was to send King Charles [Charles I] to the scaffold [with the approval of Oliver Cromwell, the Calvinist]; the new rich families who were to introduce the [Protestant] House of Hanover were already in the second stage of their metamorphosis from the freebooters of Edward VI’s reign [1547-1553] to the conspirators of 1688 [i.e., the usurpation of the Catholic King James II, or “the Glorious Revolution”] and the sceptical, cultured oligarchs of the eighteenth century. The vast exuberance of the Renaissance had been canalized. England was secure, independent, insular; the course of her history lay plain ahead: competitive nationalism, competitive industrialism, competitive imperialism, the looms and coal mines and [financial] counting houses, the joint-stock companies and the cantonments; the power and the weakness of great possessions.[27]

Especially, we might say, the burden and the weakness of “Power without Grace“![28] In the words of Saint Helena to her belabored son Constantine, who was as yet unconverted and unbaptized as an Emperor: “Think of the misery of a whole world possessed of Power without Grace.”[29] In other words, words which were earlier applied to Emperor Diocletian himself, “All the tiny mechanism of Power regularly revolved, like a watch still ticking on the wrist of a dead man.”[30] And, for sure, the well-flattered Emperor Diocletian was at the time spiritually dead and exhausted; sick of strife and persecution (perhaps like Queen Elizabeth in the end).

This, indeed, according to Waugh, was the very sentiment that Emperor Diocletian had felt when, “consumed by huge boredom,” he stepped down from imperial rule and “sickly turned towards his childhood’s home” on the seacoast of Dalmatia; for, even he had, despite his great might, almost himself suffocated “in the inmost cell of the foetid termitary of power“[31] — “Power without Grace” had consumed him, and self-sabotaging despair in the end. Mindful of all of this, Helena was, as a good mother, warning her own son, as well — and drawing him to the Catholic Faith which she herself had so gratefully and winsomely embraced.

Edmund Campion, too, was gradually drawn to the Faith. Despite his early compromises with the new Anglican Establishment and the Elizabethan Settlement of the Tudor State, he always seemed to drink from deeper sources and was especially open to Grace, even while he was at St. John’s College at Oxford, which itself was “predominantly Catholic in sympathy.”[32] That is to say, the atmosphere there was still Catholic.

In contrast to his younger contemporary, Tobie Matthew (1546-1628), who had compromised completely with “the new order” and consequently “prospered” (becoming even the Anglican Archbishop of York), Campion persistently resisted. He was different. In Waugh’s trenchant words: “Tobie Matthew died full of honors in 1628. There, but for the Grace of God, went Edmund Campion.”[33]

While Campion was still a scholar and teacher at Oxford (1555-1569), “the division was more sharply defined” between the Catholic party in the majority and the Protestant party in the ascendant; and “Campion hesitated between the two, reluctant to decide.”[34] (In 1568, however, Campion had “committed himself more gravely by accepting ordination as deacon” in the Anglican Church, a step he later very deeply regretted![35] As Waugh depicts it, Campion had wished only to be “left in peace to pursue his own studies” and to “discharge [his] duties” as “proctor and public orator, to do his best for his pupils.”[36] With unfailing acuteness once again, Waugh immediately adds: “But he was born into the wrong age for these gentle ambitions; he must be either much more, or much less.”[37]

When the persistent integrity of Campion’s troubled conscience, in decisive combination with his close study of the Church Fathers (like John Henry Newman later), led him to an ever deeper understanding of Church History and Doctrine, “the further he seemed from the Anglican Church which he was designed to enter.” But, nonetheless, “he fled and doubled from the conclusions of his reason,” for “nothing but ill was promised for him by the way he was being drawn.”[38] It was still a temptation, an incentive to further disorder, but he resisted; he did not consent to it.

By contrast, “Tobie Matthew’s way lay smooth before him” and he could very easily convince himself that a compromise was needed altogether, in the circumstances that prevailed. Indeed, as the excuse was conveniently formulated: “In a world where everything was, by its nature, a makeshift and poor reflection of reality, why throw up so much that was excellent, in straining for a remote and perhaps unattainable perfection?”[39] (With respect to the Church Fathers and their clear support for the Catholic position, Tobie Matthew had even responded to Campion’s personal query to him, as follows: “If I believed them [the Church Fathers] as well as read them, you would have good reason to ask” — i.e., to ask why I — Tobie Matthew — do not myself become a Catholic![40]) This is a fine summary, I think, of the self-deception and corruption and dishonesty of an apostate!

In the case of Campion’s other companions of Oxford, there were some less corrupt evasions of historical evidence, and truth, and other temporizing arguments, too, which were quite “acceptable to countless decent people, then and later” — fearful people who also had resigned themselves to a lower vision of life, and of what could be expected from life and should be striven for.[41] Campion, says Waugh, was not content with mere decency, however:

There was that in Campion that made him more than a decent person: an embryo in the womb of his being, maturing in darkness, invisible, barely stirring; the love of holiness, the need for sacrifice.[42]

But the Catholic atmosphere at Dr. Allen’s seminary at Douai not only later nurtured this deeper disposition of his soul; it also made him look back upon his earlier compromises and “passive conservatism” with greater severity and self-rebuke. In Waugh’s memorable words:

Martyrdom was in the air of Douai. It was spoken of, and in secret prayed for, as the supreme privilege of which only divine grace could make them worthy. But it was with just this question, of his own worthiness, that Campion now became preoccupied. There is no record of the date of his formal reconciliation with the Church, but it is reasonable to assume that it occurred immediately on his arrival from England [i.e., in June 1572, after he had witnessed at London’s Westminster Hall, “the trial of Dr. Storey, a refugee whom Cecil had has kidnapped at Antwerp and brought home to suffer in old age under an insupportable charge of treason” — perhaps a turning point in Campion’s life — and “the condemned man [like Campion himself eight and a half years later] was executed on June 1st with peculiar ferocity“[43]] From then onwards he [Campion] was admitted to the Sacraments without which he had spent the past ten or twelve years of his life [i.e., not having received since 1560 or 1562!][44]

Moreover, as of 1572, we see a deeper change, sub gratia:

From then onwards, for the first time in his adult life [in 1555, under the Catholic Queen, Mary Tudor, Campion was only fifteen years old when he first went to Oxford], he found himself in a completely Catholic community, and, perhaps, for the first time, began to have some sense of the size and power of the world he had entered, of the distance and the glory of the aim he had [now] set himself.[45] The Faith of the people among whom he had now placed himself [along with his good friend from Oxford, Gregory Martin] was no fad or sentiment to be wistfully disclosed over the wine at high table, no dry, logical necessity to be expounded in the schools; it [the Faith] was what gave them daily life, their entire love and hope, for which [Faith] they had abandoned all smaller loyalties and affections; all that most men found desirable, home, possessions, good fame, increase, security in the world, children to keep fresh their memory after they were dead.[46]

In this atmosphere and with his humility, new discernments illuminated his mind and well-formed sensitive conscience. On the premise that “contrast clarifies the mind,” as it were, it came to pass that,

Beside their devotion Campion saw a new significance in the evasions and compromises of his previous years. At Oxford and Dublin he had been, on the whole, very much more scrupulous of his honor than the majority; he had foresworn his convictions rarely and temperately; when most about him were wantonly throwing conscience to the winds and scrambling for the prizes, he had withdrawn decently from competition; but under the fiery wind of Douai these carefully guarded reserves of self-esteem dried up and crumbled away. The numerous small jealousies of University life, his zeal for reputation, his courtship of authority [or of “Power without Grace”], the oaths he had taken of the Queen’s [Elizabeth’s] ecclesiastical supremacy, the deference with which he had given to [Anglican Bishop] Cheney’s view of conformity [with “the Powers That Be”], his melodious eulogies of the Earl of Leister [Robert Dudley, one of Campion’s patrons and one of Queen Elizabeth’s lovers, as well], above all “the mark of the beast,” the ordination he had accepted as an Anglican deacon, now appeared to him as a series of gross betrayals crying for expiation, fresh wounds in the hands and feet [or Heart!] of Christ.”[47]

To sharpen the transformation and humility of Campion, Waugh deftly says:

He had come to Douai as a distinguished immigrant …. Allen [“the founder and first President” of Douai, “Dr. — later Cardinal — William Allen of Oriel, a gentleman of ancient Lancashire family, thirty-years old at the date of the foundation, 1568, who had left Oxford at the first religious changes” and had “become a priest in Louvain”][48] received him as a sensational acquisition. He [Campion] had left England, it may be supposed, in a mood of some pride and resentment; he was casting off the dust of ingratitude, taking his high talents where they would be better appreciated. Now in this devout community, at the hushed moment of the Mass, he realized the need for other gifts than civility and scholarship; he saw himself as a new-born, formless soul that could come to maturity only by long and especially sheltered growth.[49]

In the end, Campion embodied Saint Ignatius Loyola’s prayer, already cited, from his Spiritual Exercises: “Suscipe, Domine, universam meam libertatem. Accipe memoriam, intellectum atque voluntatem omnem …. (“Take and receive, O Lord, all my liberty. Receive and accept my entire memory and understanding and will”). At the end, “the composition of place” for Campion was not Calvary during the Passion of the Lord, which he had so often contemplated with love. His own Passion, in the Providence of God, would be at Tyburn; his Cross would be the Gibbet and the butcher-work to follow.

As in the case of Saint Longinus, so, too, with a witness of Campion’s later Testimony of Blood:

One man … returned from Tyburn to Grays Inn profoundly changed; Henry Walpole, Cambridge wit, minor poet, flaneur, a young man of birth, popular, intelligent, slightly romantic. He came from a Catholic family and occasionally expressed Catholic sentiments, but until that day [1 December 1581] had kept a discreet distance from [George] Gilbert and his circle [who, at great risk to themselves, sheltered and conducted support operations for the hunted missionary priests], and was on good terms with authority. He was a typical member of that easy-going majority, on whom the success of the Elizabethan Settlement depended, who would have preferred to live under a Catholic régime but accepted the change without very serious regret.[50] He had an interest in theology and had attended Campion’s conferences with the Anglican clergy [four of them, starting on 1 September 1581, after he had been put to the torture by the “rack-master” in the Tower of London — the fourth conference “to test the truth of his Creed” being held shortly before his judicial Trial for Treason began on 14 November 1581 at Westminster Hall, where Dr. Storey himself had also been condemned in May of 1572]. He [Walpole] secured a front place at Tyburn; so close that when Campion’s entrails were torn out by the butcher and thrown into the cauldron of boiling water a spot of blood splashed upon his coat. In that moment he was caught into a new life; he crossed the sea, became a priest, and thirteen years later, after very terrible sufferings, died the same death as Campion’s on the gallows of York.[51]

A recapitulation of the external events of significance and chronology of Campion’s life may be helpful at this point, especially after having considered Waugh’s more concentrated and intimate insights about Edmund Campion’s transformation unto holiness and heroism, to include Campion’s effects upon others, for their greater good. A schematic summary will serve our purpose, therefore, in an Appendix.

In the eloquent depictions of his book, Waugh moves from the final melancholy and very sad death of Queen Elizabeth, back to when as a young woman of thirty-three she first met Edmund Campion (on 3 September 1566); then to a presentation of the state of Oxford University and of Campion’s patronage (promised to him from both Leicester and Cecil), for “they had need of men like Campion” now “that the University had thrown off its lethargy and was once more advancing in hope.”[52] “But the past,” says Waugh, “could not be recalled,” for “a great tradition had been broken.”[53] Moreover, says he:

Not for a hundred years [i.e., until around 1670] was the University [Oxford, specifically] to know security [for “no one felt confidence in the rewards of scholarship” and “politics and theology continued to sway University elections”], and it was to emerge from its troubles provincial, phlegmatic and exclusive [and, most certainly, exclusive of Catholics!]; not for three hundred years was it to re-emerge as a centre of national life.[54]

It was the case, as of 1566, that

Now Cecil and Elizabeth were finding it very hard to get suitable candidates for ministry in the new church. By the first acts of the reign [of Queen Elizabeth] they had made the Mass illegal.[55]

No longer at Oxford was there to be seen “the spacious, luminous world of Catholic humanism.”[56] And, it must be remembered that

From its earliest days the University had been primarily a place for the training of churchmen. By the statutes, Holy Orders were obligatory on aspirants for almost all important offices. Sons of the aristocracy might keep term in the interests of culture, but the general assumption for poor scholars was that they were qualifying as priests.[57]

Now we may better understand Elizabeth’s and Cecil’s problem, and why they would have wanted to attract and give further patronage to Edmund Campion, even as late as November 1581, shortly before his vile and truculent execution. Even Campion’s sister was sent to him on such a mission during those last eleven days of his in the Tower of London, even as he lay in the dark dungeon in irons. In Waugh’s poignant words:

Hitherto his family have made no appearance in the story; now a sister of whom we know nothing, came to visit him, empowered to make a last offer of freedom [sic] and a benefice, if he would renounce his Faith.[58]

Leading us to another moving insight about the effects of Campion’s “heroism and holiness” — to include the forgiveness of others from his heart — Waugh adds the following:

There may have been other visitors [during those final eleven days] …. but the only one of whom we have record is George Eliot [the one who, like Judas, had betrayed and helped capture him]. “If I [Eliot] had thought that you would have had to suffer aught but imprisonment through my accusing of you, I would never have done it.” “If that is the case,” replied Campion, “I beseech you, in God’s name, to do penance, and confess your crime [to include his unmistakably base perjury at Campion’s own Trial for Treason], to God’s glory and your own salvation.”[59]

Waugh’s immediate comment is exquisite, and then compassionate and consoling, further revealing thereby the mystery of Grace and Divine Mercy — especially the grace of conversion of a hardened human heart:

But it was fear for his life [“fear for his skin”] rather than for his soul that had brought the informer [and apostate perjurer] to the Tower; ever since the journey from Lyford, when the people had called him “Judas,” he had been haunted by the spectre of Catholic reprisal.

“You are much deceived,” said Campion, “if you think the Catholics push their detestation and wrath as far as revenge; yet to make you quite safe, I will, if you please, recommend you to a Catholic duke in Germany, where you may live [were his conscience to permit it!] in perfect security.”

But it was another man who was saved by that offer. Eliot went back to his trade of spy; Delahays, Campion’s gaoler, who was present at the interview, was so moved by Campion’s generosity that he became a Catholic.[60]

By his further deft implicitness and artful indirection, Evelyn Waugh very forcefully and cumulatively conveys the inhumanity and violence of the New Elizabethan Régime and its New Religion.

For example, the founder of Saint John’s College at Oxford, Sir Thomas White, according to Waugh:

Had lived until 1564 [i.e., two years before Campion first met Queen Elizabeth], and up to his death he saw to it that the rules he had laid down were properly observed. He was a city magnate of modest education and simple piety; a childless old man who devoted the whole of his great wealth to benefactions. The last years of his life were overclouded by the change of religion; he collected the sacred vessels from the College Chapel and stored them away in his own house for a happier day, and was obliged to stand by helpless while the authorities perverted the ends of his own foundation; he saw the poor scholars whom he had adopted and designed for the [Catholic] priesthood trained in a new way of thought [i.e., in the insidious Neo-Modernism of his day!] and ordained with different rites, for a different purpose.[61]

Adding to this poignancy, Waugh says:

He had set down in his statutes that the day was to begin with Mass, said in the Sarum use; at Elizabeth’s accession it ceased, never to be restored; he saw three of his [Catholic and College] Presidents … deposed by the authorities for their faith. He died a comparatively poor man, out of favour at Court, out of temper with the times, and was buried according to Protestant rites — Campion speaking the funeral oration in terms which appear rather patronising [“The poor old man”!]. Perhaps in secret a Mass was said for him; it is impossible to say.[62]

Though there were “still many priests [of the Catholic Faith] at Oxford” in 1564, and “at this time the greater part of St. John’s was Catholic in sympathy;” nonetheless “Catholicism at Oxford was largely [then] a matter of sentiment and loyalty to the old ways, rather than of active spiritual life” — “until the counter-reformatory period, fifteen or twenty years later [1579-1584]” and the return of Father Campion, S.J.[63]

However, at this earlier time of Edmund Campion’s piercingly condescending funeral oration for the Catholic founder of his Oxford College, Thomas White — who may himself have died with a broken heart — the Council of Trent (1545-1563) had itself just ended the previous year. But, it was already clear, says Waugh, that

The official Anglican Church had cut itself off from the great surge of vitality that flowed from the Council [the Council of Trent, and Saint Charles Borromeo, for example]; it was by its own choice, insular and national. The question before Campion [also in 1564] was, not whether the Church of England was heretical, but whether, in point of fact, heresy was a matter of great importance; whether in problems of such great importance human minds could ever hope for accuracy, whether all formulations [as with the irreformable doctrines of Catholic Dogma] were not, of necessity, so inadequate that their differences were of no significance.[64]

But, what about the Catholic Mass?

For the New Régime, as is still the case today, it would seem, the primary target was the Sacrifice of the Mass, in which “Calvary is happening.” For a while, the new Anglican authorities could and would tolerate certain Catholic customs and lingering sentimentalisms:

But the saying of the Mass was a different matter …. They were united in their resolve to stamp out this vital practice of the old religion [the Actio Sacra Missae]. They struck hard at all the ancient habits of spiritual life — the rosary, devotion to Our Lady and the Saints, pilgrimages, religious art, fasting, confession, penance and the great succession of traditional holidays [i.e., Holy Days] — but the Mass was recognized as being both the distinguishing sign and main sustenance of their opponents.[65]

(We will recall that, about thirty years after he first penned these words, Waugh was to face his own ordeal over the new Liturgical Revolution within the Catholic Church, where, once again, as he saw it, the integrity of the Mass was at stake.)

As in the ongoing Dialectic Revolution today, informed, as ever, not by the principle of life, but by the “principle of disorder” — “solve et coagula!” — so, too, at the time of Campion, many well-meaning, but incompletely formed, Catholics were “dealing with the problem of conformity”[66] and also with the corrosive “solvents” of their hostile society. The Law in England was still mild (1559-1570); that is to say, until Saint Pius V’s 1570 Proclamation of Queen Elizabeth’s Excommunication and Deposition, after which time Catholics were more and more suspect of treason and potential rebellion.

Nevertheless, even under milder Penal Laws against Catholics, many of which were for a while not strictly applied, the average Catholic family had to face the threat of “sequestration,” “confiscation,” “fines,” and even (after the third offense) “imprisonment for life.”[67] Often, their choice was between either “submission” or “destitution.”[68] (Such submission often lead to apostasy; and the threat of destitution often lead to conspiracy and revolt, for the men, especially, were eventually “made reckless by injustice.”)

Moreover, says Waugh, even before the later 1570 Papal Excommunication, namely in the Spring of 1568, the Catholic Mary Stuart — “Mary Queen of Scots” — had taken refuge from the strife in Scotland, and then “was imprisoned in England.” She was seen as a threat, in many ways. For, says Waugh:

In the event of war abroad or rebellion at home, Cecil felt that the Catholics constituted a grave menace. They were proving more stubborn in their faith than had first seemed likely …. Accordingly, all over England the commissioners and magistrates were instructed to take a firmer line; at first no new legislation was used, but the law which had been administered with some tact was everywhere more sternly enforced. More Catholics went into exile, among them Gregory Martin [who went to Douai], Campion’s closest friend for thirteen years, who had left Oxford to act as a tutor in the Duke of Norfolk’s family [the head of which, himself a Catholic, had led a Northern Rebellion]. The repression had begun which was to develop year by year from strictness to savagery, until, at the close of the century, it had become the bloodthirsty persecution in which Margaret Clitheroe was crushed to death between mill stones for the crime of harbouring a priest.[69]

Thus, according to the discerning Waugh:

When Campion [while still at Oxford] most required tranquillity in which to adjust his vision to the new light [of his still slowly germinating Catholic Faith] that was daily becoming clear and more dazzling, events outside his control, both at Oxford and in the world at large, became increasingly obtrusive.[70]

Soon, therefore, he was to seek refuge in Ireland — until that, too, became more precarious: “The authorities in Dublin were instructed to arrest suspected Catholics, and at the beginning of March 1572 Campion, with his History [i.e., The History of Ireland] still unfinished, became a fugitive.”[71] But, “there is no clear record of his movements in the next few months.”[72] Eventually, by the end of June, he arrives in Douai.

Indeed, “in this ill-documented decade” (circa 1568-1580), the situation of the Catholics became increasingly difficult and sometimes confused, especially for those families who had to live on in England. Speaking with deft and vividly imaginative irony, Waugh recapitulates this situation:

The Catholics, left without effective leadership, appear to have been dealing with the problem of conformity [or, whether to choose Resistance to the growing Religious Revolution], each in his own way. It was one which varied greatly in different parts of the country. Some [i.e., those who at once became firm “Recusants”] refused the oath [of the Queen’s Spiritual Supremacy] and went into exile; some paid the penalties of the law. Some, who were popular or locally powerful, avoided, year after year, taking the oath at all; some took the oath and meant nothing by it. That generation [before the re-animating arrival of the Jesuits!] was inured to change; sooner or later [they imagined] the tide would turn in their favour again; a Protestant coup [a more radicalized strike by the Calvinists], such as was spoken of, to enthrone Earl of Huntington might inflame a national rising and restore the old religion; the Queen [Elizabeth] might die and be succeeded by Mary Stuart [Mary Queen of Scots]; she might marry a Catholic; she might declare for Catholicism herself. In any case, things were not likely [they delusively imagined] to last on their present unreasonable basis [Things were, in fact, to worsen and gravely degenerate!]. It was one thing for a government to suppress dangerous innovations — that was natural enough; but for the innovators [heretics, apostates, eclectics, syncretists] to be in command, for them to try to crush out by force [or by fraud!] historic Christianity — that was contrary to all good sense; it was like living under the Turks.[73]

In 1570-1571, too, during the reign of Pope Pius V, “the Turks were threatening Christianity from the rear, her centre was torn by new heresies, his [the Pope’s] allies were compromising and intriguing, their purpose distracted by ambitions of empire and influence.”[74] Pope Pius V’s successor Gregory XIII, also found himself constantly “reinforcing on all fronts the resistance to the Turks and the Reformers [or, rather, the Deformers of the Faith].”[75] Catholics, in their resistance and initiatives, must always be strategic, and not just tactical!

(So, too, is it the case for us now in the Twenty-First Century, but with a few additional elements and challenges now added. For now, we must deal, for example, with the difficult problem of deception and self-deception in the Church itself, as well as in the State and the Secret Societies. Hence, we must be prepared to face trust-breaking perfidy in high places. We must also be prepared to face new “psycho-techniques” of manipulation in the electronic and other “Mass Media,” which dangerously complement new methods of warfare and intimidation.)

In the Sixteenth Century, too, there came a point where faithful Catholics could no longer be “courtiers and connoisseurs” or “dilettanti,” especially “among the Catholic laity whose loyalty was already strained by persecution” amidst “the conflict that was rending every Catholic heart.”[76] When earlier referring to those more quiescent Catholics who would prefer to conform, Waugh had said: “But it needed more than a gentle heart and pious disposition to make a Catholic in that age.”[77] So, too, today!

Waugh himself, perhaps implying his own deeper examination of conscience, as well, reinforces this point:

The listless, yawning days were over, the half-hour’s duty perfunctorily accorded on days of obligation [i.e., on Holy Days of Obligation]. Catholics [after 1580] no longer chose their chaplain for his speed in saying Mass, or kept Boccacio bound in the covers of their missals. Driven back to the life of the catacombs, the Church was recovering her temper.[78]

As the Penal Laws (and their application) went further and further from “strictness” to “savagery,” in order, purportedly, to keep “the Queen Majesty’s subjects in due obedience,” other measures were taken:

In 1581, to meet the emergency of Campion’s mission, a further act [of Legislation] was passed …. It reaffirmed the principle that it was high treason to reconcile anyone or to be reconciled to the [Catholic] Church and imposed a new scale of fines …. It is the first time that the Mass is specifically proscribed …. The object of this legislation was to outlaw and ruin the Catholic community.[79]

Persons of cruelty, such as Francis Walsingham and his chief priest-hunter, Richard Topcliffe, said that they did not want “to make the bones” of a later Jesuit martyr and poet, Father Robert Southwell, “dance for joy,” and, so:

He and others like him now [under the new penal legislation] proceeded about the country levying blackmail where they could, spying, bribing servants, corrupting children, compassing the death of many innocent priests and the ruin of countless gentle families. The Catholics were defenseless at law [the Truth was not a defense], for their whole inherited scheme of life had been dubbed criminal [as if the charge, often made today, were true that Catholic Christianity itself is intrinsically “Anti-Semitic,” and thus soon to be liable under certain currently existing laws “on the books” in Europe; or the inexorable demand that certain of the Christian Gospels, especially John and Matthew, should be “expurgated” — censored — for their “hate speech” and other potentially persecutory incitements!]. They lived [and maybe, soon, we ourselves] in day-to-day uncertainty, whether they may not be singled out for persecution, their estates confiscated, their families dispersed and themselves taken to prison [and “the rack-master”] or the scaffold [as was to happen, we know, to Campion himself].[80]

But Father Campion shows us “the supernatural solution,” under Grace, and the deep, preparatory training for that higher supernatural vocation and the higher chivalry:

Both sides [Catholic and Protestant] now looked upon him [especially after “Campion’s Brag” had circulated very rapidly and had keenly animated his readers] as the leader and spokesman of the new mission; his membership of the Society of Jesus cast over him a peculiar glamour, for, it must be remembered, the Society had, so far, no place in the English tradition [and Campion himself was to become the Jesuit Protomartyr of the English Mission] …. ‘Jesuit’ was a new word, alien and modern. To the Protestants it meant conspiracy …. To the Catholics, too, it meant something new, uncompromising zeal of the counter-Reformation …. and in his place [in place of the earlier kind of “simple, unambitious” conventional priest] the Holy Father [Gregory XIII] was sending them [the vulnerable Catholics] in their dark hour, men of new light, equipped in every Continental art [of argumentation and persuasion], armed against every frailty, bringing a new kind of intellect, new knowledge, new holiness. [Jesuit Fathers] Campion and Persons found themselves [in 1580-1581] travelling in a world that was already tremulous with expectation.[81]

With the publication of the Ten Reasons (Decem Rationes — De Haeresi Desperata) in June of 1581, says Waugh, “the first part of Campion’s task was accomplished”:

He had been in England, now, for over a year; that was his achievement, that in all her centuries the English Church was to count one year of her life by his devotion; others were now ready to take over the guard; … the Church of Augustine and Edward and Thomas would still live; for Campion there remained only the final sacrifice.[82]

And it soon came — but after much intimidation and attempted seduction, striving to allure him both to “ecclesiastical” preferment and to apostasy; after much torture and his vigorous defensive debates (amidst his great fatigue) against the heretics and apostates themselves; after the travesty and mockery, as with Christ, of his ignominious Trial and Judicial Murder.

Reporting the words of Campion’s own Jesuit superior (who was six years younger than he), Father Robert Persons, Waugh gives us a piercing anticipation:

His [Campion’s own frequented missionary] road to Harrow took him past Tyburn gibbet, and here, Persons records, “he would often pause, both because of the sign of the Cross and in honour of some martyres who had suffered there, and also because he used to say that he would have his combat there.”[83]

And he did!

Just as it was the case “in the Tenebrae of his Passion” shortly after Campion had movingly preached on the Gospel Text “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, thou killest the prophets” — and just before his own final capture at Lyford Grange (in Mid-July of 1581) — Campion always kept his special qualities of courtesy and pluck, constancy and high spirits.[84] Even when, as in the Holy Week monastic ceremonies of Tenebrae, the light almost goes out — but for one final, and flickering candle — so, too, with the resilient magnanimous spirit of Edmund Campion, in combination with his deep humility. Such was the nature of his higher chivalry and daring; such was the vivid poise of his supernatural hope! The hope of the Christian martyrs.

For example, when first discussing, at Uxbridge, the important text which was finally to be called the Ten Reasons [i.e., the Decem Rationes, in Defense of the Catholic Faith],

Campion had proposed [as a title] De Haeresi Desperata — “Heresy in Despair;” it was a suggestion typical of the spirit of the missionaries; on every side heresy seemed to be triumphant; the Queen’s Government was securely in power; the old Church was scattered and broken; they themselves were being hunted from house to house in daily expectation of death; their very existence was a challenge to the power of the State to destroy a living faith. Leading Catholics, such as Francis Throckmorton, were discussing a treaty [a truce, an armistice] with the Government in which they promised to compound their fines for a regular subsidy on condition of being allowed the quiet practice of their religion. All despaired of the restoration of the Church, and only begged sufferance to die with the aid of her sacraments [in the event that they were mercifully allowed to have a “prepared-for death”]. It was at this juncture that Campion gently proposed to examine the despair of heresy and show that all its violence sprang from its consciousness of failure.[85]

In one of Campion’s own letters — a report to his Jesuit Superiors — the ending likewise conveys his pluck and hope and resilient trust:

There will never want [i.e., will never lack, be lacking] in England men that will have care of their own salvation, nor [will there be lacking] such as shall advance other men’s [salvation]; neither shall this Church here ever fail so long as priests and pastors shall be found for their sheep, rage man or devil never so much.[86]

Waugh greatly appreciated what Campion himself had gratefully recorded about his eight-day visit to Saint (then Cardinal) Charles Borromeo’s own residence and household in Milan, while they were enroute back to England on their final apostolic mission. Showing his own deeper heart, Waugh, as Campion’s biographer, could therefore also write with beauty, the following words:

The pilgrims were received, entertained, blessed [as they had also been blessed by Saint Philip Neri, when they were leaving Rome] and sent on their way, and the immense household [of the Faith] went about its duties; in its splendor and order and sanctity, a microcosm of the Eternal Church.[87]

Evelyn Waugh could also vividly render his profound gratitude to Cardinal William Allen of Douai and Rheims, who was so indispensable to Edmund Campion and to the supernatural vocations of many others down the years:

The object of the college [at Douai, and later at Rheims] was primarily to supply priests for the Catholic population, for, since the bishops were all either in prison or under detention, it was impossible for them, except very rarely with the connivance of the gaolers, to ordain priests; the system of education imposed by the Government [of Queen Elizabeth] made it increasingly difficult to train candidates for orders in England; in a few years the Marian priests [the older priests ordained during the five-year reign of Queen Mary Tudor] would begin to die out and, as [William] Cecil foresaw would quietly expire with them; that Catholicism did in fact survive — reduced, impoverished, frustrated for nearly three centuries in every attempt at participation in the public services; stultified, even, by its exclusion from the Universities [primarily Oxford and Cambridge], the professions and social life; but still national; so that, at the turn of opinion in the nineteenth century, it [Catholicism] could re-emerge, not as an alien fashion brought in from abroad, but as something historically and continually English, seeking to recover only what had been taken from it by theft — [THAT] is due, more than to any other one man, to William Allen.[88]

High tribute, indeed! And where might be the strategic-minded men of the Faith today — both in Holy Orders and among the Laity — whom we, too, may join and materially support and indefatigibly defend? The analogies between our situation today and the situation of the Faith (and of the faithful) in Sixteenth-Century England should be clearer to us now near the end of this essay. But, for us today there is also the challenge of an insidious and “peaceful preliminary subversion” on “the inner front” of the Church, in addition to more openly aggressive strategic attacks (even, as with Cecil, “a reign of terror”) upon “the exterior fronts.” Perfidy itself always breaks intimate trust. As is always the case with the Lie, its most harmful social effect is the subversion of trust. Trust, once shattered, is so hard to repair, even when forgiveness is given.

But, the Saints always show us what is possible. This is their manifold encouragement to us, as it is seen in the deepening life and final blood-witness of Saint Edmund Campion. While he was studying at Douai, says Waugh, there came to him

The continuous insistent summons to the highest destiny of all. The copy of the Summa [Saint Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae] which Campion was using at the time survives at Manresa College, Roehampton; it is annotated in his own hand and opposite an argument on baptism of blood [by Saint Thomas] occurs the single mot prophète et radieux [i.e., the single prophetic and radiant word], Martyrium.[89]

By way of conclusion, Evelyn Waugh says:

And so the work of Campion continued [as in the later martyrdom of Father Henry Walpole, who had been so unexpectedly touched by a drop of Campion’s blood]; and so it continues. He was one of a host of martyrs, each, in their several ways, gallant, and venerable; some performed more sensational feats of adventure, some sacrificed more conspicuous positions in the world, many suffered crueller tortures, but to his own [generation], Campion’s fame had turned with unique warmth and brilliance; it was his genius to express, in sentences [with a unique power of style, recalling Lactantius’ words and Saint Helena!] that have resounded across the centuries, the spirit of chivalry in which they suffered, to typify in his zeal, his innocence, his inflexible purpose, the pattern which they followed. Years later, in the sombre, sceptical atmosphere of the eighteenth century, Bishop Challoner set himself to sift out and collect the English martyrology. The Catholic cause was very near to extinction in England …. It was then, when the whole gallant sacrifice appeared to have been in vain, that the story of the martyrs [and Edmund Campion, especially] lent them strength. We are the heirs of their conquest, and enjoy, at our ease [perhaps too much, or slothfully so?] the plenty which they died to win. Today a chapel stands by the site of Tyburn; in Oxford, the city he [Campion] loved best, a noble college [Campion Hall] has risen? dedicated in Campion’s honour.[90]

May we all, therefore, in a fuller sense — and without any spiritual sloth or inordinately self-satisfied complacency — become “Campionists”[91] and come to imitate (after our own fitting and disciplined preparation) “the spirit of chivalry in which he suffered.”

Let us not, like the “Cultural Relativists” and “Liberal Historicists” today, consider, by way of trivialization and condescension, that Campion’s response was, perhaps, once an “appropriate response,” but is no longer so now, in the new age of “ecumenism” and “inclusiveness” and “convergence.”

Let us instead, too, rise up to the higher standards of our Faith — and live up to the graces we may receive — with the radiant spirit of Campion’s chivalry and spiritual childhood.

For, Our Lord came that we might have life, and have it more abundantly. The Christian Soldiers, all of us, must therefore grow up into Spiritual Childhood — which is an abundant challenge, too!

Saint Augustine of Hippo said that God created us without our co-operation, but He will not save us (or even justify us) without our co-operation.[92]

Saint Edmund Campion, Martyr, pray for us — especially for Evelyn Waugh who so gratefully cherished you.

Fifteen years after Waugh had first published Edmund Campion (1935), he published Helena (1950). In this historical novel, he presents, on the Feast of the Epiphany, a Mother’s Prayer for Her Son, and for all other “Late-Comers” to Christ, like Helena herself — and Edmund Campion, too:

While addressing the Three Magi, with whom she closely identified, who were also “Late-Comers” to Christ, Helena memorably says:

“You are my especial patrons,” said Helena, “and patrons of all late-comers, of all who have a tedious journey to make to the truth, of all who are confused with knowledge and speculation, of all who through politeness make themselves partners in guilt, of all who stand in danger by reason of their talents.

“Dear cousins [as my Patron Saints], pray for me,” said Helena, “and for my poor overloaded son [i.e., Constantine the Roman Emperor]. May he, too, before the end find kneeling-space in the straw [i.e., beside the creche of Christ]. Pray for the great, lest they perish utterly ….

“For His sake who did not reject your curious gifts, pray always for the learned, the oblique, the delicate. Let them not be quite forgotten at the Throne of God when the simple come into their kingdom.”[93]

–FINIS–

© 2006 Robert Hickson

CODA

By way of further encouragement, and as an illustration of Evelyn Waugh’s special charm and comic touch of gracious irony throughout his inspiring, but very serious, book on Edmund Campion, this short addition proposes to do three things: (1) to give Campion’s own description of the Irish, selected from his own History of Ireland, which he wrote while in Dublin (late 1579-March 1572); (2) to give Waugh’s characterization of a very special man, the “ever impetuous” Mr. Thomas Pounde (the man who wisely suggested “Campion’s Brag” to him and later even became a Jesuit himself!); and finally, (3) to give Waugh’s depiction of a certain Father Bosgrave, S.J., who had been surprisingly sent from the Polish Province of the Jesuits, in 1580, to England, and sent for his health and for some rest and recreation!

Campion’s description of the “mere Irish,” especially fitting to be read on Saint Patrick’s Day, was written before he became a Catholic. It is charming, and perhaps even a little provocative! In Campion’s own words, Ireland was “much beholden to God for suffering them to be conquered, whereby many of their enormities were cured, and more might be, would [they] themselves be pliable”![94] The further “flavour” of Campion’s vivid history of the Irish people may be savoured, with cheerfulness, from the following two excerpts, which were presented — and warmly appreciated — by Waugh, as we may well imagine:

“The people are thus inclined: religious, frank, amorous, ireful, sufferable, of pains infinite, very glorious [perhaps like a “miles gloriosus“!]; many sorcerers, excellent horsemen, delighted with wars, great almsgivers, passing in hospitality. The lewder sort, both clerks and laymen, are sensual and loose to lechery above measure. The same, being virtuously bred up and reformed, are mirrors of holiness and austerity, that other nations [including the English!] retain but a show or shadow of devotion in comparison of them.”[95]

Now comes Campion’s brief description of the men of Ireland, and of their women:

Clear men they are of skin and hue, but of themselves careless and bestial. Their women are well favoured, clear coloured, fair headed, big and large, suffered from their infancy to grow at will, nothing curious of their feature and proportion of body“!![96]

There follows, now, Waugh’s own description of Mr. Thomas Pounde, “impetuous as ever,” and a worthy future Jesuit:[97]

They [Father Campion, Father Persons, and the others] arrived at nightfall [in Hoxton, near London, to the north] and were about to start out again the next morning when they were met by Mr. Thomas Pounde, who had slipped prison [in the Marshalsea] and ridden after them. Pounde was a devout and intelligent man, of pronounced eccentricity. The circumstances of his religious conversion were remarkable. He had been born with wealth and powerful family connections, and for the earlier part of his life lived modishly and extravagantly at Court; his particular delight was in amateur theatricals, for which the fashion of the reign gave him ample scope. On one occasion he performed an unusually intricate pas seul before the Queen; it made a success with her and she called for a repetition. He complied, but, this time, missed his footing and fell full length on the ball-room floor. The Queen was more than delighted, gave out one of her uproarious bursts of laughter, kicked him, and cried: “Arise, Sir Ox.” Pounde picked himself up, bowed, backed out among the laughing courtiers with the words: “Sic transit gloria mundi,” and from that evening devoted himself entirely to a life of austere religious observance. Various attempts, friendly and penal, failed to draw him back to his former habits, and in 1574 he was put in prison, after which date he was seldom at liberty, except on rare occasions like the present one.[98]

Finally, with regard to another Jesuit, we may savour Evelyn Waugh’s quite inimitable irony and comic style (his tonal diction, word order, and sense of incongruity): the case of Father Campion’s contemporary, Father Bosgrave, S.J., who, coming from Poland, had a surprise visit to England! Waugh’s presentation of his case is, as follows:

There was also the case of Father Bosgrave, another Jesuit, who had joined the Society sixteen years before and had since been working in Poland, far out of touch with the course of events in England. Now, at his superiors’ bidding, he returned to England, sent, by a singular irony, for the good of his health [in 1580!]. He was arrested immediately he landed, and taken for examination to the Bishop of London, who asked him whether he would go to church. “I know no cause to the contrary,” he replied, and did so, to the great pleasure of the Protestant clergy, who widely published the news of his recantation. The Synod [of Catholics, at Southwark] had only time to express their shame at his action before it broke up. The Catholics all shunned him, and Father Bosgrave, who retained only an imperfect knowledge of English, wandered about lonely and bewildered. Eventually he met a Catholic relative who explained to him roundly the scandal which he was causing. Father Bosgrave was amazed, saying that on the Continent scruples of this kind were not understood, but that a Catholic might, from reasonable curiosity, frequent a Jewish synagogue or an Anabaptist meeting-house if he felt so disposed [i.e., without thereby being guilty of an illicit participatio in sacris, or worse!]. As soon as it was made clear to him that the Protestants had been claiming him as an apostate, he was roused to action, and, saying that he would speedily clear up that misunderstanding, wrote a letter to the Bishop of London which had the effect of procuring his instant imprisonment. He was confined first in the Marshalsea and later in the Tower, from which he was moved only to his trial and condemnation for high treason, a sentence that was later commuted to banishment. He then returned to Poland and resumed his duties there, having benefited less by his prolonged stay in England than his superiors had hoped.[99]

APPENDIX

1540 — Campion, the future Protomartyr of the English Jesuits, is born in London, on 25 January — a man in whom, finally, as in all the Saints,

“the grace of Christ is victorious” (Father Constantine Belisarius of Front Royal).

1555-1569 — Campion is at Oxford University from the age of fifteen until almost thirty (Queen Mary Tudor dies in 1558; Elizabeth ascends to the throne.)

Late 1569-March 1572 — Campion settles in Ireland, as a scholar, in the Anglo-Irish home of one of his former students at Oxford. He writes his The History of Ireland there, in English, not Latin. (He knew no Gaelic.)

Early June 1572 — Campion’s departure from England, after only a brief return to his homeland; and he is then enroute to the Douai Seminary in Flanders, under Dr. William Allen.

June 1572-January 1573 — Campion is in residence and study at Douai Seminary, in Flanders.

February 1573-April 1573 — His arrival in Rome and subsequent departure for Vienna, Brunn, and Prague after being accepted into the Austrian Province of the Society of Jesus.

May 1573-25 March 1580 — Campion’s six years of residence in Prague (with a short, initial period in Brunn) in the Jesuit Noviciate; and as a concurrent Professor of Rhetoric and later a Professor of Philosophy, as well as a producer of dramas, especially tragedies, for the stage. He was ordained as a priest and said his first Mass on 8 September 1578, in Prague.

9-18 April 1580 — Campion is in Rome again, preparing for the Mission back to England. He takes leave of, and receives a blessing from, Saint Philip Neri himself.

18 April-15 June 1580 — Campion is enroute to Rheims, France by way of Florence, Parma, Milan (with eight days at the residence of Saint Charles Borromeo), and then on to Turin, into the Savoy, and through Geneva itself (“the home of Calvinism”), where they had several courageous and even humorous experiences!

24 June 1580 — Campion lands at Dover, England “before it was daylight.”

29 June 1580 — Feast of Saint Peter and Saint Paul. Campion celebrates Mass in London, preaching on the theme “Tu es Christus, Filius vivi Dei” and “Tu es Petrus.”

Late July 1580 — Campion writes in his own hand the Manifesto of his mission, his Challenge, “Campion’s Brag.”

27 June 1581 — Campion’s Decem Rationes (Ten Reasons, which was originally to have been called De Haeresi Desperata — Heresy in Despair) is placed, in multiple copies, in the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin at Oxford University — intentionally timed for distribution at the University Commencement ceremonies.

16-17 July 1581 — Campion is captured at Lyford Grange, near Lyford, in Berkshire.

20 July 1581 — Campion is enroute to London as a prisoner, by way of Abington and Henley, to the Tower of London.

End of July 1581 — Campion, after four days in solitary confinement, is rowed upstream from the Tower of London to the Leicester House, for an interview with Queen Elizabeth herself, in the presence of her advisers: the Earl of Leicester (Robert Dudley), William Cecil (Lord Burghley), and the Earl of Bedford (Francis Russell), who was Cecil’s Brother-in-Law.

5 Days Later, 1581 — Leicester and Burghley, having failed to corrupt him, sign the official warrant to put Campion “to the torture,” to include “the Rack,” in the Tower of London.

September-November 1581 — Campion endures, amidst great fatigue and pain, four Theological Conferences and Examinations before the Anglican Clergy, so that “Campion’s challenge, contained in the Brag and the Ten Reasons, should not go unanswered” (Waugh).

14 November 1581 — Campion’s Trial for Treason commences, along with the trial of seven other priests, with their formal Arraignment. “A majority in the [Privy] Council had already decided in favour of Campion’s execution” (Waugh). It was, therefore, to be a “Mock-Trial” — a fake and a travesty.

20 November 1581 — The Trial for Treason formally took place. “It was now abundantly clear that there was to be no fair trial.” (Waugh) Campion was found guilty and condemned to go the gallows and to the butcher-work that follows.

21 Nov.-1 Dec. 1581 — “Campion lay in irons [in the Tower] for eleven days between his trial and his execution,” during which, unsuccessfully, “his sister tried to get him to renounce his Faith” (Waugh).

1 December 1581 — At Tyburn, Campion is martyred for the Faith, with his companions, Father Sherwin and Father Briant. “It was raining; it had been raining for some days, and the roads of the city were foul with mud” and “Every circumstance of Campion’s execution was vile and gross” (Waugh).

1886 Edmund Campion is beatified by Pope Leo XIII.

25 October 1970 Edmund Campion is canonized by Pope Paul VI, and is given a Feast Day of 1 December, the day of his courageous and humiliating Martyrdom.

Pater Edmundus Campianus, Martyr

[1] Evelyn Waugh, Edmund Campion (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1946), p. 160. This 1946 edition is the second edition, the first edition being published in 1935 with notes and bibliography, which are unaccountably missing from the 1946 edition. His book was gratefully dedicated to Father Martin D’Arcy, “to whom, under God, I owe my faith.”

[2] Evelyn Waugh, Scott-King’s Modern Europe (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1949), p. 89.

[3] See A Bitter Trial: Evelyn Waugh and John Cardinal Heenan on the Liturgical Changes (edited by Scott M.P. Reid) (London, England: The Saint Austin Press, 1996). Waugh was sixty-two years of age when he died on 10 April 1966.

[4] Evelyn Waugh, Edmund Campion (1946 edition), pp. 83 and 32, respectively.