The Author’s Introductory Note (Written on 13 July 2021):

The following recent (7 July 2021) comment, composed by Dr. Peter Kwasniewski in his essay for Crisis Magazine, has inspired my decision to publish (along with some of the contributions from my wife Maike) my earlier and searching, if not candid, essay of 18 May 2018. That essay (below) is ten pages in length, with many varied quotations, and it is entitled Joseph Ratzinger on the Priesthood and on the Resurrection.

We may, after some close reading, thereby come to understand much better certain forms of applied Hegelianism active in the Catholic Church. For example, Dr. Kwasniewski has himself observed and said: “Indeed, Benedict XVI’s work is often characterized by an Hegelian dialectic method that wishes to hold contradictories simultaneously, or to seek a higher synthesis from a thesis and its antithesis (‘mutual enrichment’ can be understood in this [Hegelian] framework).” (“Summorum Pontificum at Fourteen: Its Tragic Flaws” (page 6 of 8 pages)—my emphasis added)

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

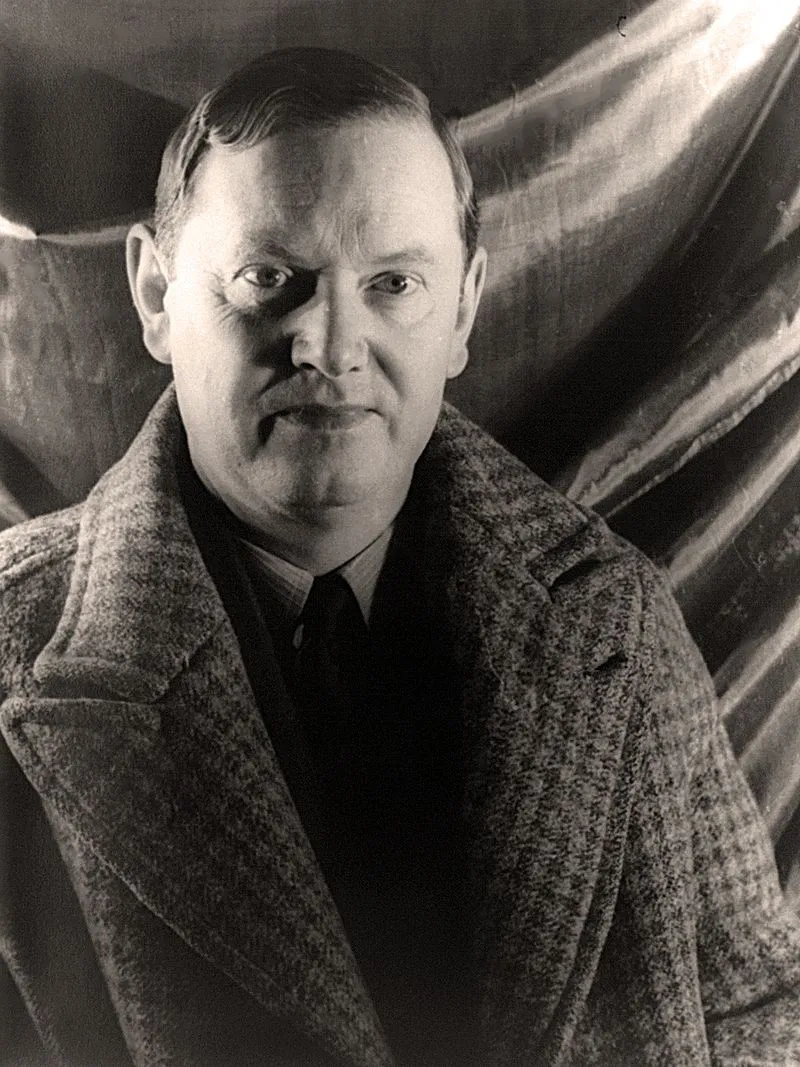

Dr. Robert Hickson

18 May 2018

Saint Eric (d. 1160)

Epigraphs

“But the point is that Christ’s Resurrection is something more, something different. If [sic] we may borrow the language of the theory of evolution, it is the greatest ‘mutation,’ absolutely the most crucial leap into a totally new dimension that there has ever been in the long history of life and its development: a leap into a completely new order which does concern us, and concerns the whole of history.” (The Easter Vigil Homily of Pope Benedict XVI, Holy Saturday, on 15 April 2006, in the Vatican Basilica—my emphasis added)

***

“The Resurrection was like an explosion of light, an explosion of love which dissolved the hitherto indissoluble compenetration of ‘dying and becoming.’ It ushered a new dimension of being, a new dimension of life in which, in a transformed way, matter too was integrated and through which [integration and new dimension] a new world emerges.” (Pope Benedict XVI’s Easter Vigil Homily on15 April 2006, Holy Saturday)

***

“It is clear that this event [i.e., the Resurrection] is not just some miracle from the past, the occurrence of which could be ultimately a matter of indifference to us. It is a qualitative leap in the history of ‘evolution’ and of life in general towards a new future life, towards a new world which, starting from Christ [a Divine Person?], already continuously permeates this world of ours, transforms it and draws it to itself.” (Pope Benedict XVI’s Easter Vigil Homily, on 15 April 2006, Holy Saturday)

***

“The great explosion of the Resurrection has seized us in Baptism so as to draw us on. Thus we are associated with a new dimension of life into which, amid the tribulations of our day, we are already in some way introduced. To live one’s own life as a continual entry into this open space: this is the meaning of being baptized [sic], of being Christian. This is the joy of the Easter vigil. The Resurrection is not a thing of the past, the Resurrection has reached us and seized us. We grasp hold of it, we grasp hold of the risen Lord, and we know that he holds us firmly even when our hands are weak.” (Pope Benedict XVI’s Easter Vigil Homily, on 15 April 2006, Holy Saturday)

***

In the latter part of 2006, after the April 2005 installation of Joseph Ratzinger as Pope Benedict XVI, I had occasion to tell a professor friend of mine confidentially that I have always had difficulties reading with understanding the varied writings of his German friend who is now the Pope. In seeking to understand Joseph Ratzinger’s language and his undefined theological abstractions (about relation and mutation and communion and the nature of the Church), I admitted my own incapacity and perduring insufficiency.

Acknowledging my difficulties, my compassionate and learned friend—who is also himself an admirer and personal friend of Joseph Ratzinger—said to me, and quite unexpectedly: “He is often too subtle for his own good.” I promptly replied: “And for our good, too, … or [I added] at least for my own good!”

For example, the arcane language used by Pope Benedict on Holy Saturday — even in his Easter Vigil Homily on 15 April 2006 — should be considered and slowly savored, first of all in the four Epigraphs I have chosen for this essay. But, by way of objection, one might say that these Epigraphs are not at all representative of Joseph Ratzinger’s mind and essential writings, especially not the seeming echoes or optimistic atmosphere of Jesuit Father Teilhard de Chardin (d. 1955) with his own evolutionary and naturalistic language about mankind’s “biocosmic possbilities,” about “an ongoing revelation,” “the evolution of Dogma,” and other purported developments beyond the contingencies of human history and our sinful propensities, and even beyond “the hope of the Christian martyrs.”

However, some well-informed scholars have also said that Joseph Ratzinger’s thought—even the earlier Teilhardian influence — has not essentially changed down the years; and, more importantly to me, Ratzinger has never yet made any public retractions, or formal Retractationes, of his own statements, as Saint Augustine himself had so humbly done in his candidly written and promulgated volumes.

Therefore, before we may more fittingly discuss Pope Benedict XVI’s Easter Vigil Homily on 15 April 2006—Holy Saturday—in Saint Peter’s Basilica of Rome, we should consider what a lauded priest-scholar, Karl-Heinz Menke—who himself specializes in Joseph Ratzinger’s many writings—has to say1 about the special continuity and consistency of Ratzinger’s thought and presentations. This priest and emeritus professor of Bonn University now recapitulates his own observations and reflections, as follows

There is barely any theologian like the retired pope [stepping down as of February 2013], whose thinking has remained constantly the same over decades. What he demanded before and during the Council [1962-1965], he still demands today. […] Joseph Ratzinger has self-critically asked himself whether he has contributed with his theology to the post-conciliar breach of tradition. But it is not known to me that he revised any position of his theology.

However, in Joseph Ratzinger’s 16 March 2016 published Interview with the Jesuit theologian, Father Jacques Servais2—himself a student of the former Jesuit, Hans Urs von Balthasar and a scholar of his voluminous works—the retired pope very forthrightly says (also for the later-published 2016 book, Through Faith, by Jesuit Father Daniel Libanori), as follows:

If [sic] it is true that the [Catholic] missionaries of the 16th century were convinced [sic] that the unbaptized person is lost forever—and this explains their missionary commitment. After the [1962-1965 Second Vatican] Council, this conviction was definitely abandoned, finally. The result was a two-sided, deep crisis. Without this attentiveness to salvation, the Faith loses its foundation. (my emphasis added)

Benedict had first explicitly said: “There is no doubt that on this point we are faced with a profound evolution of dogma.” (Some, like Father Gregory Baum, might have even more subtly called it “a discontinuous development of doctrine.”) But then Benedict’s own integrity here soberly admits: “If faith and salvation are no longer interdependent, faith itself becomes unmotivated”! (my emphasis added)

Benedict, by speaking of a “profound evolution of Dogma” implicitly concerns himself with the Church and with the Dogma “Extra Ecclesiam Nulla Salus,” in contradistinction, for example, to a vaguer and more attenuated formulation, such as “Sine Ecclesia Nulla Salus.” In the retired pope’s eyes, this purported change of dogma (irreversible doctrine) has clearly led to a loss of missionary zeal in the Church. Indeed, he says, inasmuch as “any motivation for a future missionary commitment was [thereby supposedly] removed.” About this allegedly altered new “attitude” of the Church, Benedict poses an incisive question: “Why should you try to convince the people to accept the Christian faith when they can be saved without it?” (my emphasis added)

Moreover, if there are those who can still save their souls with other means, “why should the Christian be bound to the necessity of the Christian Faith [and of the Catholic Church] and its morality?”

On an intentionally more positive note, Benedict then turns to one of his heroes, Father Henri de Lubac, S.J., the now-deceased, and very learned scholar and Jesuit Cardinal who was himself a defender and supportive friend of Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J. More specifically, Benedict rather arcanely turns to de Lubac’s putatively sound and exploratory insight about Christ’s “vicarious substitutions,” which, says Benedict, have to be now again “further reflected upon.” Benedict optimistically hopes that de Lubac’s own expressed—but quite abstract—idea of “vicarious substitutions” will somehow lead us out of our above-mentioned “two-sided, deep crisis” in the Catholic Church, the fruit of the new attitudes and logic coming out of Vatican II and its Aftermath. (Benedict himself never even defines what de Lubac means by his utopian and unconvincing abstraction, “vicarious substitutions,” as the key criterion!)

In this context, some earlier comments made to me in person by Professor Josef Pieper and by Father John A. Hardon, S.J.—and made to me privately in the mid-1970s and mid-1980s, respectively—will also now help us frame our present inquiry concerning Joseph Ratzinger’s enduringly influential, if not disorienting, thought. That is to say, Ratzinger’s own proposed “Integra Humana Progressio,” as it were: which is usually also officially translated as “integral human development.”

Sometime in 1974 or 1975, and in his own library at his home in Münster in Westphalia, Dr. Pieper showed to me a letter from Joseph Ratzinger that was signed “Dein Ratzinger.” And then Dr. Pieper told me that there was a story behind that letter. It had to do with Father Joseph Ratzinger, a young professor at the University of Münster during the interval 1963-1966; until he went to teach dogmatic theology at the University of Tübingen (where Hans Küng was his colleague).

While Father Ratzinger was in Münster, Josef Pieper had a Catholic Reading Group at his own home at Malmedyweg 4, and Ratzinger was regularly present at those meetings and searching discussions about fundamental things, such as “What is a Priest?” That is to say, what is the essence of the sacramental Catholic Priesthood.

Dr. Pieper told me that he and Father Ratzinger had a serious exchange about the essence of the sacramental priesthood. Dr. Pieper said emphatically that, in order to make his point, Ratzinger even used a very unusual formulation in German. With a challenge, the young Father Ratzinger said: “A priest [essentially] is not a mere Kulthandwerker”—that is, he is not a mere craftsman of the cultus (the Church’s visible and public worship, especially in the Mass).

Dr. Pieper objected to Ratzinger’s claim, he told me, although he also found Ratzinger’s word-formulation exceedingly odd and so abstract as to be largely unintelligible to the ordinary speaker of the German language. However, Dr. Pieper then said that “the essence of a priest was indispensably to be a Kulthandwerker, uniquely offering the sacrificial ‘actio sacra‘ of the Holy Mass, but also sacramental absolution in the unique Sacrament of Penance.”

After Dr. Pieper explained to me the larger context and the aftermath of that discussion, he showed me the mid-1970s handwritten German letter from Ratzinger himself, where he said (in my close paraphrase) that “it is a good thing that we can disagree, and yet still be friends. Your Ratzinger [“Dein Ratzinger”].” For, it was also true that, sometime in the 1970s, Josef Pieper had already published a learned academic article about the priesthood that had—without mentioning Ratzinger by name—strongly criticized Ratzinger’s own limited concept of the priesthood as well as his odd, shallow use of the incongruous conceptual word “Kulthandwerker.”

Dr. Pieper later wrote brief and lucid books on the priesthood, on the meaning of the sacred, and also on the “sacred action” (“actio sacra”) of the Mass. However, I know nothing more of the likely later-written exchanges between Josef Pieper and Joseph Ratzinger; and Dr. Pieper never again brought up that adversarial topic with me over the many years that we knew each other and wrote to each other (1974-1997).

In the late 1980s, some fifteen years after Dr. Pieper’s disclosure to me in his library, I was comparably surprised and deeply enlightened by Jesuit Father John Hardon’s words to me in person and to another Jesuit priest who had telephoned him in my presence. It occurred in Father Hardon’s own room at the Jesuit Residence of the Jesuit University of Detroit, in Michigan. For, I was making a Private Ignatian Retreat with him, having flown out to Detroit from Front Royal, Virginia.

One evening, our retreat was politely interrupted by the editor, Father Joseph Fessio, S.J.’s somewhat lengthy telephone call to Father Hardon from California at Ignatius Press. Straightaway, Father Fessio asked Father Hardon to write some endorsing comments on one of their new English translations, specifically Urs von Balthasar’s short book, Dare We Hope that All Men Be Saved (1988). Father Hardon immediately declined to do so, and gave Father Fessio his reasons: “Joe, there are at least three heresies in that book—despite its title’s allusion to 1 Timothy 2:4.” Father Hardon (“John”) then explicated at length those errors he was referring to, to include von Balthasar’s view on “the Sources of Revelation,” the “Proximate Norm of Faith,”and on “Universal Salvation, Apocatastasis,” and other troubling affirmations or deft equivocations. Father Hardon was himself a Dogmatic Theologian and very attentive to the full Catholic doctrine of “Divine Grace” and, especially, to “Divinely Revealed Sacred Tradition,” in addition to “Divinely Revealed Sacred Scripture.”

Although I could say much more about this portion of Father Hardon’s words to Father Fessio, it seems fitting (“conveniens”) now to mention what John Hardon earnestly said to Joe Fessio—after he had once again urged him to be a “settler”and more rootedly come to earn finally, after many years, his own protective and academically acquired “Fourth Vow” in the Jesuit Order—and he spoke not only to an editor, but also to a devoted former student under Joseph Ratzinger: “Joe, why are you now also publishing so many new books by Joseph Ratzinger, especially so many of his earlier writings, such as his 1968 book, Introduction to Christianity? Why does Joseph Ratzinger want to bring up his past?” (Father Fessio then said that Ignatius Press would soon publish, but only in 2000 actually, a second revised version of that 1968 book, Introduction to Christianity, but with no retractions or recantations.)

After the phone conversation—where I had been sitting on a chair close to him—Father Hardon and I had a lengthy memorable discourse about these same matters of subtle Neo-Modernism, to include a consideration of Pope Pius XII’s own short but important 1950 Encyclical, Humani Generis.

Father Hardon also memorably spoke about two closely related errors: an evolutionary “process philosophy” and an evolutionary “process theology.” In the first, “the Geist [Spirit] needs us to complete itself”–as in some forms of “Hegelian evolutionary pantheism.” The claims of emerging “process theology” are more “blasphemous” inasmuch as it boldly claims—or at least implies– that “God needs us to complete Himself.” We also then spoke of some of the evolutionary ideas of Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J. and their influence in the Church.

In 1987, Joseph Ratzinger published in English, again with Father Fessio’s Ignatius Press, his important and self-revealing 1982 book, Principles of Catholic Theology: Building Stones for a Fundamental Theology. (His lengthy, and often viscous, book was originally published in German in 1982—one year after he was summoned to Rome as a Cardinal in order to be the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith—and his German text was itself entitled Theologische Prinzipienlehre.)3 Because of its candid insights and claims—even about Don Quixote—I heartily recommend that a Catholic read, in full, at least Joseph Ratzinger’s “Epilogue: On the Status of Church and Theology Today,” and especially pages 367-393.

In a briefer selection of passages now, we thus propose to present some of the representative sections of that challenging, even stunning, book. For example:

Is anything left but the heaped-up ruins of unsuccessful experimentations? Has Gaudium et Spes [the Vatican II text, i.e., “Joy and Hope”] been definitively translated into luctus et angor [“grief and anguish”]? Was the Council a wrong road that we must now retrace if we are to save the Church? The voices of those who say that it was so are becoming louder and their followers more numerous. Among the more obvious phenomena of the last years must be counted the increasing number of integralist groups in which the desire for piety, for the sense of the mystery, is finding satisfaction. We must be on our guard against minimizing these [“integralist”] groups. Without a doubt they represent a sectarian zealotry that is the antithesis of Catholicity. We cannot resist them too firmly.4 (my emphasis added)

Ratzinger had earlier written these additionally revealing words:

Of all the texts of Vatican II, the “Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et spes)” was undoubtedly the most difficult and, with the “Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy” and the “Decree on Ecumenism,” also the most successful.

If it is desirable to offer a diagnosis of the text [of Gaudium et Spes] as a whole, we might say that (in conjunction with the texts on religious liberty and world religions) it is a revision [sic] of the Syllabus [of Errors] of Pius IX, a kind of countersyllabus. This is correct insofar as the Syllabus established a line of demarcation against the determining forces of the nineteenth century: against the scientific and political world view of liberalism. In the struggle against modernism this twofold demarcation was ratified and strengthened. Since then many things have changed….As a result [of these unspecified “changes”], the one-sidedness of the position adopted by Pius IX and Pius X [was] in response to the new phase of history inaugurated by the French Revolution….

Let us be content to say here that the text [Gaudium et Spes] serves as a countersyllabus and, as such, represents on the part of the Church, an attempt at an official reconciliation with the new [revolutionary?] era inaugurated in 1789. (378, 381-382—my emphasis added)

This should remind us also of how Ratzinger himself especially helped to found in 1972 the more moderate progressivist Journal, Communio, so as to be an alternative to the much more radical modernist-progressivist Journal, Concilium, first founded in 1965—seven years earlier. One may think of the seemingly more moderate Girondins or Mensheviks. The Communio group appears to propose a “tertium quid”—a more civilized “third way” in the moderate middle; and thus places themselves on a spectrum that is somewhere “between the Integrists and the Modernists.” But without drifting into the new subtleties of Neo-Modernism! (That would itself be a good Quaestio Disputata!)

In his own theological book, Joseph Ratzinger adds another affirmation, as it were:

That means that there can be no return to the Syllabus [of Pius IX; and even to the anti-modernist Syllabus of Pius X, perhaps?], which may have marked the first stage in the confrontation with liberalism and a newly conceived Marxism but cannot be the last stage. In the long run, neither embrace nor ghetto [sic] can solve for Christians the problem of the modern world. The fact [sic] is, as Hans Urs von Balthasar pointed out as early as 1952 [two years after Pius XII’s Humani Generis], that the “demolition of the bastions” is a long-overdue task. (391-my emphasis added)

These passages from Principles of Catholic Theology (1982, 1987) will prepare us to understand Ratzinger’s later (2006) East Vigil homily as the Pope himself, as well as his later 2016 interview touching upon certain qualms of conscience he has, after all, about Vatican II.

See, for example, Benedict XVI’s new interview-book—first released on 9 September 2016 by his German publisher Droemer Verlag and entitled Benedikt XVI: Letzte Gespräche (Benedict XVI–Last Conversations). Dr. Maike Hickson—when the book was still only available in the original German language—wrote a 7-page exposition and general review of the book’s specific Chapter on the Second Vatican Council.5

In Pope Benedict XVI’s 2006 homily in Saint Peter’s on Holy Saturday—at the Easter Vigil Mass with the deacon’s chanted “Exultet”—he resorts to some unusual words and arcane ideas. One might even think that he, too, like his friend Hans Urs von Balthasar, is still interested in carrying out the purportedly needed “task”: the “demolition of the bastions” and the consequential attenuation of traditional boundaries.

From the chosen texts in our “Epigraphs” at the beginning of this essay, we now propose to give some of those specific examples again, and thereby substantiate the estrangement we experience, and the resulting and justified discomfiture of our own “Sensus Fidei.” In any case, one should, by all means, read the entirety of this remarkable 2006 homily, which is still to be found on the Vatican website.6 But let us now consider our chosen representative excerpts:

It [i.e., Christ’s Resurrection] is the greatest “mutation,” absolutely the most crucial leap into a totally new dimension that there has ever been in the long history of life and its development: a leap into a completely new order….The Resurrection was like an explosion of light, and explosion of love which dissolved the hitherto indissoluble compenetration of “dying and becoming.” It [“the Resurrection”] ushered a new dimension of being, a new dimension of life in which, in a transformed way, matter too was integrated and through which [integration and new dimension] a new world emerges….

It is clear [sic] that this event [i.e., “the Resurrection”] is not just some miracle from the past, the occurrence of which could be ultimately a matter of indifference to us [sic]. It is a qualitative leap in the history of “evolution” [as distinct from human “history” in Joseph Pieper’s own differentiated and proper understanding?] and of life in general towards a new future life, towards a new world which, starting from Christ, already continuously permeates this world of ours, transforms it and draws it to itself [sic]….

The great explosion of the Resurrection has seized us in baptism so as to draw us on. Thus we are associated with a new dimension of life [sanctifying grace?] into which, amid the tribulations [sins?] of our day, we are already in some way introduced. To live out one’s life as a continual entry into this open space; this is the meaning of being baptized, of being Christian. This is the joy of the Easter vigil. The Resurrection is not a thing of the past, the Resurrection has reached us and seized us. We grasp hold of the risen Lord, and we know that he holds us firmly even when our hands are weak. (my emphasis added)

If I could, I would say to Joseph Ratzinger: “I don’t understand you at all. This all seems to me an abstract different religion. I wonder how many in your audience were warmly touched to the heart.”

CODA

Offering his reader a Parable involving Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Joseph Ratzinger chooses to conclude his lengthy book allusively, and somewhat symbolically, especially by affirming Don Quixote’s deepest chivalric Code of Honor:

But, as the novel [Don Quixote] progresses, something strange happens to the author [Miguel de Cervantes]. He begins gradually to love his foolish knight….[Something, perhaps Grace] first made him fully aware that his fool had a noble heart; that the foolishness of consecrating his life to the protection of the weak and the defense of truth had its own greatness. [….]

Behind the foolishness, Cervantes discovers the simplicity [i.e., Don Quixote’s sincere “simplicitas” or “oculus simplex”]….He [Don Quixote] can do evil to no one but rather does good to everyone, and there is no guile in him….What a noble foolishness Don Quixote chooses as his secular vocation: “To be pure in his thoughts, modest in his words, sincere in his actions, patient in adversity, merciful to those in need and, finally, a crusader for truth even if the defense of it should cost him his life.” (392—my emphasis added)

Ratzinger acknowledges in Don Quixote “the purity of his heart” (392) and then returns to his manifest “foolishness”: “Indeed, the center of his foolishness…is identical with the strangeness of the good in a world [also in the sixteenth century] whose realism has nothing but scorn for one who accepts truth as reality and risks his life for it.” (392) Such is the nobility of Don Quixote, and of Cervantes too; and may we also come to show and sustain such qualities ourselves, and in our children. For, there must be a vivid “consciousness of what must not be lost and a realization of man’s peril, which increases whenever…[there is] the burning of the past….those things [like Sacred Tradition] that we must not lose if we do not want to lose our souls as well.” (392-393—my emphasis added)

Since Joseph Ratzinger, as well as Josef Pieper, greatly admires Monsignor Romano Guardini, I have thought it good, in conclusion, to present Guardini’s brilliant insight about true tragedy—also affecting the Church, as in the decompositions [or “demolitions”] of Vatican II, to include the aftermath of some of its own openly posed, but untrue, principles:

The true nature of tragedy…lies in the fact that good is ruined, not by what is evil and senseless, but by another good which also has its rights; and that this hostile good [a lesser good] is too narrow and selfish to see the superior right…of the other [the greater good], but has power enough to trample down the other’s claim.7

–Finis–

© 2018/ © 2021 Robert D. Hickson

1See here Menke’s comments in German http://www.kath.net/news/62834;erman: and here some excerpts in English: https://onepeterfive.com/vatican-news-editor-claims-benedicts-gave-approval-to-letter-publication/

2See here a shorter report on this interview: https://www.lifesitenews.com/news/pope-emeritus-benedict-says-church-is-now-facing-a-two-sided-deep-crisis; and here for the full translation of the whole interview: https://insidethevatican.com/news/newsflash/letter-16-2016-emeritus-pope-benedict-grants-an-interview/

3For a fuller presentation of Ratzinger’s thoughts, see also here an earlier essay, entitled: “A Note on the Incarnation and Grace: For the Sake of Fidelity” (2017): http://catholicism.org/the-incarnation-and-grace.html

4Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Principles of Catholic Theology: Building Stones for a Fundamental Theology (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1987), pp. 389-390—my emphasis added. All further page references to this book will be placed in parentheses above, in the main body of this essay.

5This important review—with many quoted passages—may now be found at Onepeterfive.com, under the title “Benedict XVI Admits Qualms of Conscience about Vatican II” (26 September 2016): http://www.onepeterfive.com/benedict-xvi-admits-qualms-of-conscience-about-vatican-ii/. Dr. Maike Hickson’s translation from the German shows some of Joseph Ratzinger’s seeming doubts about Vatican II, especially its effects on the Catholic missions and on the faithful conviction about the uniqueness, necessity, and salvific indispensability of the Roman Catholic Church.

6See the text of the entire homily (http://w2.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/homilies/2006/documents/hf_ben-xvi_hom_20060415_veglia-pasquale.html), and ZENIT News Agency (16 April 2006) has a short report on this homily (https://zenit.org/articles/resurrection-yields-a-new-world-says-pope/). The entire homily may be found and downloaded HERE from the Vatican website itself

7Roman Guardini, The Death of Socrates (Cleveland, Ohio: The World Publishing Company, 1962, first in 1948), p. 44.